Weathering the storm and keeping perspective in New York City

Daily Relay | On 29, Oct 2013

photo credits: bytheresa.com

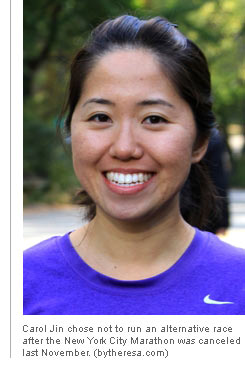

“If a canceled marathon is the biggest thing I’m worried about in any given day, I’m pretty darn lucky.”

When the New York City Marathon was scrapped less than 48 hours before its schedule start last fall, many of the more than 45,000 to-be participants experienced something like the Five Stages of Loss and Grief.

There was denial – this isn’t happening; anger – nobody understands the work we’ve put in; why punish us? bargaining – I’m going to run the course anyway, or let’s do a marathon in the Central Park loop or maybe sign up for Philly; then depression and finally acceptance.

Amid a larger life-and-death tragedy, the race cancellation was still a small-scale trauma for many runners (not to mention a huge financial hit to many of the pros scheduled to run). Plenty of them had traveled from around the world, spent months training, depriving themselves of sleep and fun and spending a lot of money to take part in the biggest – and most expensive – major marathon in the world. Having that taken away is a loss.

Somehow, though, while many took months to work through the stages of loss, Carol Jin, the 30-year-old New Yorker quoted to open this piece, seemed to zoom to acceptance with poise and perspective.

“There was a lot of anger in some of my fellow runners, and I totally understand it,” she said. “I was super disappointed, but I don’t know that a lot of them went about their feelings in the right way.”

In case you need a refresher on what happened in the week before the 2012 New York City Marathon that wasn’t, Hurricane Sandy converged with other weather patterns to form a “Superstorm” that ravaged shoreline of New Jersey, Staten Island and Long Island.

Power went out across wide swaths of the region, including all of lower Manhattan, after sea water breached the shore and poured into transformer stations. On the ocean-facing side of Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island, Long Island and New Jersey, scores of people lost their cars, homes, and ultimately more than 100 would lose their lives.

Soon after the storm passed on the Monday before the race, attention focused on the recovery. Yet there was still this matter of the world’s largest road race just five days away. Without a clear picture of how extensive the damage was and the recovery would be, many thought the race would surely be canceled while others assumed that it would have to go on, what with thousands flying in from around the world and so much money and effort already spent.

After working tirelessly to make sure the course was safe for competitors and fans, New York Road Runners and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, under mounting media pressure, announced the event’s cancellation Friday afternoon.

After working tirelessly to make sure the course was safe for competitors and fans, New York Road Runners and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, under mounting media pressure, announced the event’s cancellation Friday afternoon.

The following day, New York Road Runners emailed club members and fans to elaborate on the cancellation, referring to the “extensive and growing media coverage antagonistic to the marathon and its participants,” which “created conditions that raised concern for the safety of both those working to produce the event and its participants.”

There had been rumors that protestors would block the course to prevent runners from passing. Still, the response – presumably penned or approved by Mary Wittenberg, president and CEO of New York Road Runners – was viewed as petulant and out of touch.

“I really sympathize with her position, because she really loves New York Road Runners and she loves the sport of running,” said Jin. “I don’t think she intended to make a decision that was potentially hurtful. … I give her the benefit of the doubt and I believe she has the best interests of running at heart.”

Jin thought the cancellation made sense, even as other professional sporting events – like an NFL game at the Meadowlands on the same day as the canceled marathon – were being held in the city.

“I think that the fact that this race takes place and starts in Staten Island and that it went through some of the neighborhoods that were affected by it — it just crossed a line that the others didn’t,” said Jin. “I knew those other sporting events were going on — I was just disappointed. The amount of resources it takes to put a marathon on, it’s just a totally different scale. I don’t know that the marathon would have felt the same if I knew that people were suffering.”

That weekend, runners gathered in Central Park – many wearing their bright orange race shirts or a shirt indicating the faraway country from which they had traveled to not run the New York City Marathon. Many posed for pictures at the finish, and some even staged informal races the next day – either along the original course or entirely within the park.

“I did not run a marathon in Central Park like other people did,” said Jin, who didn’t run at all that weekend. “I didn’t sign up for another marathon, ’cause honestly, New York was the one I wanted to run.

“If marathon training is really about the journey and not the destination, then it’s not as though the training was a waste. I was still in really great shape,” she continued. “I still learned a lot about myself and got to see how disciplined I could be.”

It’s nearly a year later, a week before the 2013 race. Central Park is full of the usual tourists, dog walkers, handsome cab drivers, cyclists and, of course, runners. The sun is out, the temperatures cool, the wind minimal.

Jin, clad in a purple top and hot pink trainers for a Sunday afternoon run, heads out to tackle the hilly six-mile loop, which has already begun to transform itself into a sporting venue. Running south down the West Side, Jin crossed the New York City Marathon’s finish line (heading the opposite direction).

The uphill finish of the marathon was taking shape, with bleachers under construction, trailers and fences all around. A mile farther along the loop, Jin was back on the marathon course (still heading in the opposite direction) moving up Cat Hill on the East Side of the park. At the crest of the hill, as well as the others on the loop, Jin cheered herself and raised her arms in mock triumph, an audition for what she hopes will happen less than four hours after her 10 a.m. start on Sunday.

Running by feel, Jin goes at a comfortable 9:00-per-mile pace, starting at about 9:20 pace before dropping all the way to the 8:30s for her final mile, a negative split for sure, though she’s not actually timing herself and is only casually acquainted with terms like “negative split.”

She seems poised to break four hours in her second marathon, perhaps even challenging 3:50 on the deceptively difficult course (she ran 4:11:05 in her lone previous marathon, in New York in 2011). Not bad for someone who never ran before lacing them up in 2008.

“I first started running about five years ago after my parents were diagnosed with cancer at about the same time,” said Jin, whose parents are both in remission. “It was a way for me to deal with the stress of their treatments, because you just need sneakers and a road.”

Jin and her sister, Eunice, 28, both ran in 2011 for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society’s Team in Training (and will again this year). Their father, a leukemia survivor, was in the stands at the finish to watch his daughters cross, something that “still makes me teary thinking about it,” said Carol.

She and Eunice, an account manager at Facebook who ran 3:57:55 in her 2011 debut, are roommates in their Hell’s Kitchen apartment where Carol experiments in the kitchen, becoming a good-enough cook to win an employee recipe contest at her company, Unilever, where she is an associate finance manager. Because of her victorious “fajitos,” instead of spending her taper fretting and fussing, she took a three-day trip to Napa Valley for lessons and cooking immersion at the Culinary Institute of America.

But just days out, she’s “super excited” for her next challenge in less than a week. To inspire her during the race, she’s planning to write on her wrist the names and location of family and friends who will be cheering her on along the course.

The epitome of Jin’s approach to running is that in a spot where many runners will keep detailed splits to ensure they stay on pace, she’ll be making sure that she can share the experience with those closest to her.

“I would love to beat my time from two years ago, but most important is to just have fun,” said the relentlessly positive Jin. “First thing I remember about the marathon from two years ago is high-fiving the kids around the course and just really getting into the spirit of each borough.

“I live in the city, so it’s my hometown in a lot of ways,” added the native of Glen Cove on Long Island. “There’s something about the energy in the city that’s just unparalleled. … It’s the police officers, it’s the churches, it’s the school kids, marching bands. I don’t know how many events in the city have that sort of turnout where people of all different socio-economic backgrounds come together.”

“That sort of turnout” is why the event couldn’t be run last year. The city was suffering and fractured. A year later and getting back in shape, New York can show it’s back on its feet and moving, ready to have some fun over 26.2 miles.

Submit a Comment