Danny Mackey Got His Dream Job--Now the Hard Part

Kevin Sully | On 26, May 2015

Danny Mackey sits on the floor of the Occidental College gymnasium with his shoes off. Around him, much of the elite American distance running community waits. Coaches and athletes have filled up the dimly lit basketball court on the campus of the Los Angeles college.

Lightning and rain have forced them into this spot. It’s a little before 8:30 p.m. and the Hoka One One Middle Distance Classic has been postponed for 30 minutes.

Runners in need of a warm up or cool down are jogging the perimeter of the court, weaving around the banquet tables that are set up for the school’s upcoming commencement festivities. Mackey is seated shoulder-to-shoulder with the rest of the meet’s participants against a wall. His shoes are off in an attempt to dry his feet after stepping in a puddle outside.

The attraction of this meet — with its promise of good weather and good competition — is the fast times. The quality competition was there, but the weather continued to devolve throughout the evening, putting the rest of the races in limbo. Eight of the 11 athletes Mackey is coaching at the meet have already competed. He wonders about the impact the delay will have on the other three. Mostly though, he wants to get back outdoors.

At this precise moment, it’s hard to tell that this is Mackey’s dream job. At 34 years old, he’s the head coach of the Brooks Beasts Track Club, a daunting job, not just because he had no major coaching experience prior to taking the job two years ago, but because of the number of athletes under his watch–14 in total.

Mackey has no assistant coach or strength and conditioning coordinator. At the meet in Los Angeles, it’s just him and 11 of his athletes. The size of the team is unique and so is Mackey’s emphasis on the group dynamic. They meet for workouts together in Seattle six days a week where they are based. Members of the team often come early and stay late to support their teammates at meets. They have team meals. He refers to them as a team, not a training group.

The coach-to-athlete ratio is more what you would expect at the collegiate level. Professional groups tend to be smaller.

But big is what Mackey wanted. Not just because he ran on large, inclusive track teams in high school and in college in Illinois, but because he sees power in the collective to propel each individual member. It’s a team-based model in a sport that is ruggedly individual.

“Athletes leave college and they don’t have that [team aspect] anymore, and some people like that, and I think that’s totally fine, and I think that works for a good reason,” Mackey said.

“I want the athletes to be like, ‘OK, I really like this team component of college, you know — I like that support, I like that kind of extended family.’ What we do is try to take that and then try to be top 10 (in their events) in the world.”

Mackey always wanted to coach. If he wasn’t a runner, then he would have ended up coaching wrestling, lacrosse, basketball or whatever sport he played. He’s intrigued by the science and the psychological aspects of the job, and also by the personal interactions and high stakes of coaching elite athletes.

His sophomore year of high school he devoured every book he could find about running. He remembers one book he found in the school library that had one page dedicated to each coach’s favorite workouts. Mackey never returned it.

After competing at Eastern Illinois University, he attended grad school at Colorado State to get his master’s in Heath and Exercise Science and set up a career in coaching. “The first thing I did when there is I went to the head coach at Colorado State [Del Hessel] and I said I want to coach. I don’t care how it is going to work out time-wise, I want to do it.”

It was a struggle. In 2004, he began applying for coaching jobs with the NCAA. He didn’t get any interest. Over the next nine years, he applied for more than 200 coaching jobs and only got a single interview. He kept track of all the rejections.

While Mackey waited for his opportunity — and coached athletes individually on the side — he gained experience in other areas. He worked in the sports performance divisions for several shoe companies. He helped develop Derrick Rose’s shoes while at Adidas. When he worked in the sports research and innovation lab at Nike, he was able to witness the training systems of soccer clubs Manchester United and FC Barcelona when they visited Portland. Mackey kept all of these experiences in the back of his head for the day when he could get his opportunity to lead a team. The individual attention and the structure of the team — he wanted both and he thought he could do it with mid-distance runners.

In 2013, Brooks launched the Beasts. Mackey, who was already coaching a small group of athletes, including his wife Katie, was selected to lead the group. His diverse experience, persistence and connections to Brooks (he ran briefly for the Hansons-Brooks professional team) helped him land the job.

Three of his athletes set personal bests that summer. Those performances lent much needed credibility, though if he wanted a true team, he needed more runners.

“I know when they hired me they were like, ‘Who the heck is Danny?’ Me not having a name, the only way I was going to recruit is based off the way people were running that year.”

The group quickly expanded from a handful to a dozen, and, by the beginning of the 2014, Mackey had 14 under his watch. Nick Symmonds, the silver medalist in the 800 at the World Championships, signed on in January. Twelve run for the Beasts; the other two, Phoebe Wright and Brie Felnagle, are sponsored by other shoe companies but train full-time with the group. Members of the team run the gamut of middle distances, from 800-5,000 meters and includes recent college graduates to veterans who have been running professionally for almost a decade.

Coaching them is a man who looks young enough to be their teammate. Swap out his jeans for a pair of running shorts on race day and Mackey blends right in with his athletes.

Katie Mackey wins the 1,500 at the Hoka One One Middle Distance Classic (Photo:Track and Field Photo)

There have been challenges. Recruiting has been tough. Brooks isn’t as well known as other brands, and Mackey doesn’t have the name recognition from his own running career. Agents, he says, are more likely to the guide athletes to a bigger brand where they have a larger client base. Last year, the four athletes Mackey targeted opted to run somewhere else.

There is also uncertainty. He still wakes up in the middle of the night and wonders about whether to change the weight training routine. As much as he believes in the team approach, running is an individual sport. Those individual needs take time to address and mean long hours at the track or in the weight room. After the team grew in size in early 2014, Mackey compared it to a start-up — a huge workload at the beginning while attempting to become sustainable. There have been some changes to the roster since last year, but the core of team has remained intact.

As the team grows, Mackey is up front about how much he still needs to improve. He consults with fellow coaches like Terrence Mahon, Stuart McMillian and sprint and jump guru Dan Pfaff–he has learned something useful from all of them.

Mackey’s contract with Brooks expires in 2016 after the Olympics. He doesn’t want to go back to developing shoes, but he’s still unsure if he has done enough to establish himself. “I have to prove myself because, in my opinion, I have a dream job,” Mackey says. “I don’t have 15 years of coaching experience and Olympians. If they don’t do well, I’m probably done.”

The first test for the team came last year and the results were encouraging. Katie Mackey placed third in the 1,500 at the USA Championships. In the same meet, Cas Loxsom finished second in the 800.

“I knew that coming out of college I wanted to stay in as much of that team environment as I could,” Loxsom said after the race. “It really helps me stay accountable and work hard. We meet everyday….. We lift together, we live together, we have meals together. It’s just such a great environment.”

Loxsom backed those performances up during the indoor season this winter, where he set an American record in the 600 and also won the US Championship.

“I look at other sports teams that are really successful — they have that sense of greater purpose versus of doing things for the individual,” Mackey said.

The team concept factors into training and racing. At the 1,500 in the US Championships last year, Garrett Heath and Riley Masters planned a strategy that was mutually beneficial for both athletes in the race. Heath went to the front to control the pace and Masters to the back. They finished ninth and seventh, respectively. Not a dream finish, but the tactics gave them the best chance at a good race.

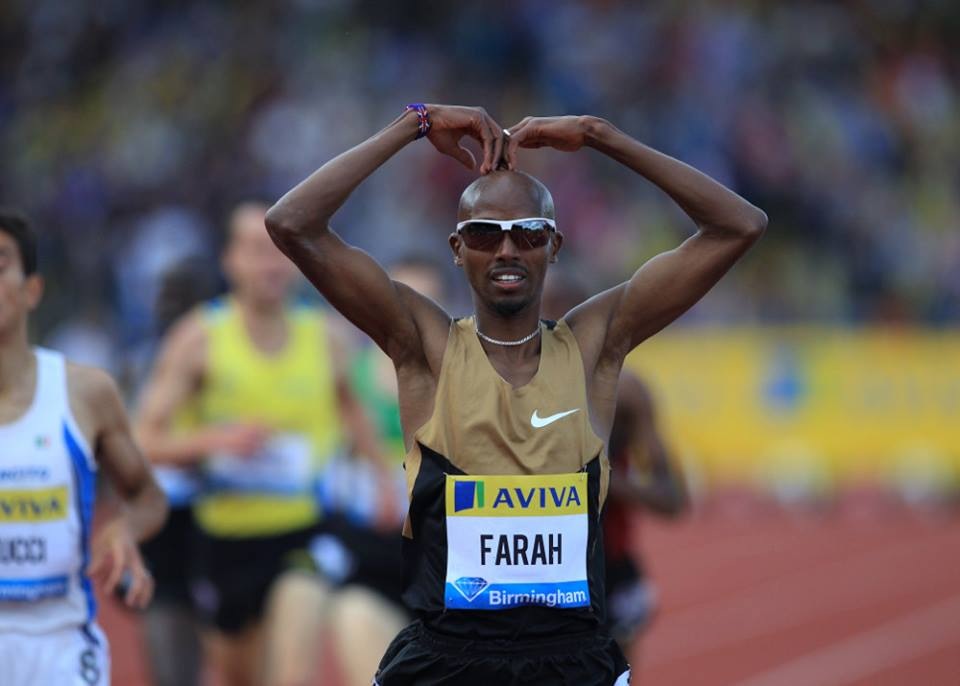

Anyone who watched Mo Farah and Galen Rupp finish 1-2 in the Olympic 10,000 in 2012 knows that teammates can help with in-race execution. Mackey thinks it goes deeper. Being part of the team, he argues, helps when it comes time to manage the stress of an important competition. “The psychological behavioral aspect is more impactful and influential than just running with someone because they are faster.”

On the mental side of coaching, Mackey’s first inspiration came from outside of the running world. Like most kids growing up in the 1990s in the south suburbs of Chicago, Mackey was enthralled by the Chicago Bulls’ run of six NBA Championships in eight years. Coach Phil Jackson was famous for managing egos like Michael Jordan, and later, Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant, but he perhaps did his greatest work molding the mercurial personalities of Dennis Rodman and Ron Artest/Metta World Peace. Mackey absorbed every word of Jackson’s book Sacred Hoops.

“You can’t lift a twig with just one finger. You need finger and thumb,” he says quoting Jackson. “I think about the team in that way — you can’t do anything by yourself.”

Jackson’s zen approach has some crossover appeal in track and field.

Danny Mackey talks with Megan Malasarte after her 800

Danny Mackey talks with Megan Malasarte after her 800

At the meet at Occidental College on May 14, Mackey is a one man show. Before the storm, he played the role of psychologist, physiologist and even equipment manager. Some of his runners like to talk with him before the race and review race strategy; others don’t. He has 11 athletes set to compete. By comparison, the Nike Oregon Project has seven athletes competing and three members of their staff at the track.

Though it is early in the season, this meet is important. In Mackey’s estimation this is one of the three remaining opportunities for American middle-distance runners to run a fast time before the US Championships at the end of June. Fast times mean qualification standards, invitations to higher-profile meets and more opportunities for athletes. All of that is swirling in the air as the last remaining bit of blue sky over the track turned deep grey.

The meet gets off to an eventful start for the team. Cas Loxsom discovered that he forgot his jersey at the hotel. Another athlete grabs it for him and brings it to the meet. Mackey runs it across the track to him while Loxsom is warming up.

In the women’s 800, Phoebe Wright finishes fifth in 2:02.18. Mackey says the race, “couldn’t be any worse tactically.” He allows Wright to vent when he meets up with her in the infield. There are silver linings though, Wright ran faster than she did at this meet last year and, despite the positioning errors, she felt strong throughout the race. The tactics can be adjusted, he says.

Two heats later in the 800, Megan Malasarte finishes last in 2:06.54. Unlike Wright, Mackey thinks her challenge is physiological. This is her first year on the team and her body had a negative response to the altitude training when the team trained in Flagstaff, Arizona. Mackey thinks they need to test her ferritin levels when they get back to Seattle.

It soon becomes clear that, when you have 11 athletes competing, something is going to go wrong. Something is also going to go right. Often, both happen in the same race. The success and setbacks blend together.

Loxsom wins his heat of the 800 in 1:46.23. In the same race, Symmonds had to evade a runner who fell and finishes seventh.

Cas Loxsom holds of Matthew Centrowitz to win the 800 (Photo: Track and Field Photo)

Mackey is relaxed and composed throughout. He mostly stays on the backstretch and times his bathroom trips so he doesn’t miss a race. Before each race, he clears his watch out of habit. “I don’t know why I do that. I always think that I’m going to look at splits, but I never do.” For an exciting race, like the men’s 800, he runs across the field to get a closer view of the finish.

After the 800s, the 1,500 is up on the track. The women’s 1,500 is particularly important. Katie Mackey is second on the waiting list for the Prefontaine Classic. A win or a fast time here and she could be added to the field. Danny is brief with his comments before the race, “Pay attention to mechanics. … Have fun.”

One lap into the race, a runner falls. “That’s the stuff that stresses me out,” he says.

Mackey embodies the plight of the helpless track coach. Once the gun sounds and the race begins, the coach can yell and scream, but he has no real way to impact the race. They can’t call a timeout. He can’t adjust strategy or scheme midway through. Some coaches offer encouragement; some stay silent. All coaches have a feeling of powerlessness that what is done is done. Coaching running is an exercise confined to the front end — preparation, timing of workouts, scheduling of races. All of that, they can control.

With 400 meters remaining, Katie is in second place. She looks composed when she runs past her husband for the final time, much like she did two years ago when she won this race and set a personal best. At the top of the homestretch, she grabs the lead.

“Keep on the gas… Keep on the gas… Keep on the gas,” Danny mutters to himself.

Katie holds off the field and wins her heat in 4:07.51.

After the race she credits the “Oxy magic.” While she gives post-race interviews, Danny watches the next heat. To win the $2,500 prize — and have the best chance at getting into the Prefontaine Classic — she needs the fastest time of the night.

He jokes about the wind dying down as the second heat begins. Early in the race, it looks like that someone in this race will beat Katie’s time. As they finish, he checks the clock. The winner, Sarah Brown, runs 4:09.00. Katie has the fastest time of the night.

“All right — that’s a win,” he says.

But he can’t celebrate for long– another rookie, Amanda Mergaert, doesn’t run well in the final heat of the women’s 1,500. The rain and lightning soon follow. Everyone at the meet is herded into the gymnasium.

A 30-minute delay stretches to 80 minutes as water pools up on the track. Runners, athletes and supporters were moved first from a metal tent on the track to Occidental’s gymnasium and then finally to a dance studio. The mood shifts between disbelief, frustration and resignation. The dance studio is lined with runners trying stretch out their legs. Someone brings in a bag of Jack in the Box fast food and all it’s unwelcomed aromas. A few runners from Mexico pose for a picture with Alberto Salazar.

Eventually, meet organizers decide to cancel the remaining races. Felnagle, Matt Hillenbrand and Dorian Ulrey won’t get to race. All three needed this race as an opportunity to achieve a qualifying standard for the USA Championships meet at the end of June.

The races scrapped, Mackey and the other coaches are scrambling. He begins constructing an email on his phone to agents and meet directors to get his athletes into a replacement race in the next few weeks. The time window is small. Athletes have until June 14th to meet the standard. He thinks a meet in Canada on June 8 might take them, but it’s too soon to tell.

At 9:30 p.m. Mackey is still in the dance studio. The last people emptied out five minutes ago, though he didn’t seem to notice. One final email sent, he heads back out into the rain.

-

Great work Danny!

-

Great read. GO Danny and the Beasts!

Comments