The Land of the Rising Run

Daily Relay | On 12, Aug 2014

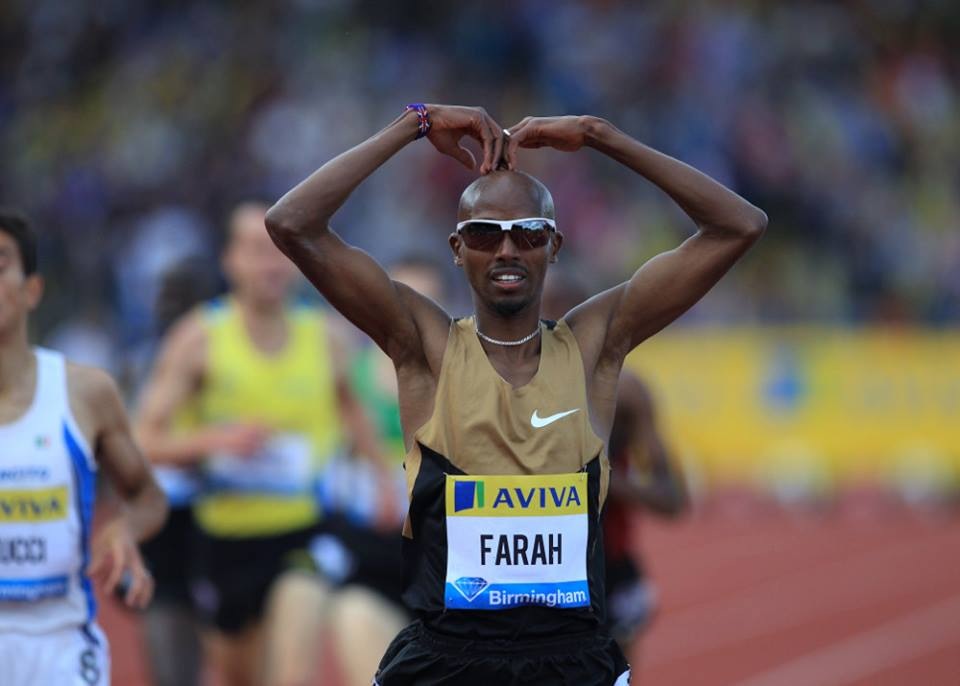

Photo: Michael Lebowitz

In a place called Track Town USA, a novice runner rarely garners much attention. Eugene has earned this nickname from the feats of Steve Prefontaine, Alberto Salazar, and Kathy Hayes among a long list of others contending for American records and national crowns. Aaron Porter is not on that list, yet his pilgrimage through the Mecca of running has produced a following nevertheless.

He is 43 years old, well beyond the prime age of a competitive runner. At 6’2” and 200 pounds, he more closely resembles a gorilla in physique than the gazelle-types who float along the surface of nearby Hayward Field. When I first met Porter on a February night at a middle school track, the members of the Eugene Flyers had more modest goals. The local training group age ranges from 30 and 50 years old with most are seeking to simply improve their fitness. Some may attempt the marathon. It is improbable that any will reach such heights as their coach, Ian Dobson, an Olympian in the 5000 meters. The cameraman filming from the infield, however, has come for Porter. His appearance is gruff. A few weeks removed from a head and face shave, he’s simply dressed in unbranded fun-run schwag. Porter is rather inconspicuous compared to the swooshed and flashy athletes like Dobson, who’ve put Eugene on the map.

In early January, Porter posted a video to his blog announcing his intention to run the length of Japan to raise funds and awareness for the 2011 tsunami victims. The media took chase following Porter’s New Year’s resolution. A week later he was profiled by the local ABC affiliate, and the following week he was on air with a pop radio station. Tonight, the camera a few feet from the track belongs to a University of Oregon journalism club.

His lumbering stride doesn’t suggest he’s built for the 20-mile runs in the days ahead, but his coach is confident. It’s the management of logistics—and of emotions—that will be the most taxing. Porter’s strength and determination is apparent when seeing him share the lead of 800 meter repeats with a training partner. Then again, the scale of Porter’s run is much grander than next weekend’s 5k, which is but one facet that attracts a myriad of journalists and elevates an ordinary man into the limelight—the other is his hapless circumstances.

“If the whole thing were bankrolled it would be way less interesting,” says Dobson.

Midway through his third tour around the oval, his training partner surges ahead, leaving Porter in No Man’s Land. All outcomes equally possible, he could go either way.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Porter attended high school in Vancouver, Washington, dabbled in track & field, and worked at K-Mart. After closing, Porter and his older co-workers would habitually migrate across the street to a bar. He held odd jobs following graduation before pursuing a career in radio at stations from western Washington to southern Oregon. Throughout it all, however, his chief position was as an alcoholic.

“Drinking is what I did. It just so happened I worked in an industry—radio—that was more than welcoming to have this partier representing their product. That’s the lifestyle. That’s the demographic. And I just took it to the next level.”

That next level was using Yukon Jack as mouthwash, cracking his first beer the last hour of work and finishing two others before going off-air until he could get to a bar.

“I never saw past my own desire to drink,” says Porter, but others saw the deleterious effects.

One morning his mother noticed a clump of grass hanging off the bumper from an unremembered off-road incident but at first made little of it. His friends made special arrangements for their hangouts, stocking the fridge with extra beer out of necessity. He wasn’t a mean drunk, but sometimes it caused him to be gregarious to the degree of offense. With few remaining enablers at 27, Porter was greeted instead with an intervention.

“I hadn’t hit rock bottom, but I was skimming it,” says Porter.

By his own admission, Porter is gung-ho with his endeavors. As such, when tasked with sobriety, he attended Alcoholics Anonymous willingly. Porter still recites the Serenity Prayer on occasion, but otherwise gained little from meetings. He had trouble relating to the dire circumstances that brought others there and lacked an overall sense of belonging.

“I was only feeling better about myself because I was comparing myself to them.”

Porter knew he had been poisoning himself with alcohol–and still was, as a pack-a-day smoker–but he had little to share with another attendee who admitted to injecting alcohol directly into his veins.

Gradually, Porter fell in with another group of addicts—distance runners. Just as he had with alcohol consumption, his indulgence began modestly. His first foray into running came from wanting to spend more time with his wife who was enrolled in Team In Training. Six weeks later he completed the San Diego Marathon in a modest five hours, but by then he was hooked, and shaved two hours off his following race in Seattle. In many cities, runners are relegated to back roads and secluded trails. In Eugene, the running addiction is so rampant that packs of thinly-clad mileage junkies commandeer sidewalks and dirt paths in full exhibition. Porter runs with many in this crowd, and the Flyers are just one group he joins as often as his frenetic schedule allows.

Most people Porter’s age have established themselves in life; he is starting over. In 2009, his DJ shift was replaced with syndicated programming. Following this, Porter enrolled at the University of Oregon to study Public Relations and still works as a laborer for the athletic department. Along with students half his age, Porter balances term projects with maintaining the grounds at one of the most esteemed venues in all of running, Hayward Field. School and work are constantly changing, yet it suits him.

“If I’m not staying busy, and I think too much about things, I get a little bummed about my situation. I’d rather stay busy than sit there and sulk,” says Porter, “I’m taking it one day at a time.”

The nights are likewise changing. Porter and his wife of 13 years, who helped him get sober,recently divorced and he lives between friend’s couches. With the majority of his paycheck going to tuition, rent is beyond his means.

“Dealing with life on life’s terms,” as opposed to turning to the bottle for escape, “is the hard part,” says Porter.

The constant in his life is running, and home is with the Flyers and the University of Oregon Running Club. Running is a personal source of relief and recovery. As he dodges stones underfoot, he turns over others in his mind. The span of a long run allows him to mull over his uncertainties, his fears, his insecurities.

“I’ll know that I had that moment out there and that was all me,” having exhausting himself both physically and mentally.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

Porter’s undertaking to run the length of Japan alone is a herculean effort. Balancing this venture with his current personal affairs seems nearly impossible. When I spoke to Porter weeks later in April, he sounded weary. He’s just had cysts removed from his throat, graveling his otherwise smooth broadcaster’s voice.

“I’m pretty horrible at planning, and this is requiring a good deal of it. I’m much more of a ‘go and do’ as opposed to plan everything out.”

He has raised only a fraction of his goal. He has not enlisted a support crew for the three month journey, hasn’t arranged lodging and hasn’t learned Japanese. The result of his announcement six months ago is greater awareness to the idea. With six months to go, little has been accomplished to make it a reality. No one is more aware of the shaky circumstances than Porter himself.

“There’s all that pressure if you don’t get it done, [the attention] has been for nothing. I got to get it done.”

Having such conviction in the face of adversity is expected when there is a personal connection. For Porter, who has no link to Japan, it is inexplicable. There’s no Japanese heritage, no previous life-changing trip to Japan, no long-lost pen pal. He does not recall March 11, 2011 as a personal hallmark, when the massive earthquake rocked inland Japan. Yet the resulting deaths of more than 19,000 people and the displacement of another 136,000 predicate his life now.

Following the tsunami, the Japanese government estimated the total cost of the damage exceeded $300 billion. Were Porter to fundraise within a tenth of a percent of this, he would exceed most expectations yet have little overall effect. In fact his $35,000 goal contributes as much as doing nothing at all after his own expenses are covered. What’s more, the fantasy that a stoic people will line the streets for an American is misconceived. Especially one who equates an act of God with alcoholism or running for relief. There’s a sense, then, that Porter is jousting at windmills.

None of which is meant to suggest Porter is a fraud nor is deliberately deceptive. He isn’t. Porter has more encouragement for a stranger running a mile than he’s had for himself during these last few years. Then you understand what running Japan means to him. Running allowed him to run away from a past. It kept him grounded, and it’s the one thing he controls as things fall apart.

Porter’s effort may be misguided, but he should be supported. For those who believe all others running for charity are personally responsible for alleviating the afflicted, it’s they who are delusional. Porter will not save thousands who are displaced, but in supporting his efforts to do so he may be saved.

In half a year the world will learn whether one can help many or many can help one. In the meantime, Porter has the serenity to accept the things he cannot change, the courage to change what he can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

Raised in Eugene, Jon Terzenbach currently lives in Connecticut and writes at onthepen.com.

Submit a Comment