College Track Issues & Answers: Popularity, and who wins outdoors?

Jesse Squire | On 17, Mar 2015

Filling these stands took a lot more work than most people realize.

The weekend in college track was all about the national championships. If you want a recap, the USTFCCCA has you covered.

Before the weekend’s action began, I was asked the following:

FL and OR may battle for the NCAA title but only go head to head in one event. Is this a reason track isn't more popular? @tracksuperfan

— Linh Nguyen (@CoachLinh) March 12, 2015

Coach Nguyen was referring to the fact that Oregon’s men had NCAA qualifiers in the weight throw, mile, 3000, 5000 distance medley, while Florida’s men had qualifiers in the 200, 400, 800, 5000, 4×400, long jump, triple jump and shot put. As mentioned, the overlap was just one event.

I tweeted a few responses, but my full thoughts on this cannot fit into 140 characters or even 1400.

My first reaction was to think about this in terms that a coach or athlete would understand very well by drawing comparisons to training. Wondering if track and field is not popular because of its national championships format is somewhat akin to wondering if you could raise an athlete’s performance level merely by changing his/her training over the last two weeks of the season. That’s ridiculous. Athletes’ overall performance levels are determined by what they do for the months and years leading into the season, not what they do in the last few weeks. The same holds true for track’s popularity. What matters most is what we do for the weeks and months leading into the championship. Reversing the trend will take far more than tinkering around the edges.

Track and field in general, and college track in particular, is not as popular as it could be because being popular is not a priority for the sport’s decision makers. It took a long time for track to decline in popularity and when (or if) it’s decided that it’s important to do more than mere lip service to change that, then it will take a long time to move the needle in the other direction.

Building fan interest is a long and arduous process, and keeping it should not be taken for granted. Let’s take a look at the place that calls itself Track Town, USA. It’s easy to think that track is popular in Eugene because it always has been popular in Eugene, but it’s far more complex than that.

When Bill Bowerman first arrived at the University of Oregon in 1949, interest in Duck track and field was not notable, and especially not notable by the standards of the post-WWII west coast, where USC and Cal and Stanford and UCLA often ran in front of home crowds of more than 10,000. It was not until his twelfth season on campus (1960) that the Ducks first drew a home crowd of more than 5,000 fans. The sweat and toil that went into building that fan base is well documented in Kenny Moore’s Bowerman and the Men of Oregon. Bowerman got out into the community and busted his behind in order to get people interested in his teams, and it is by far his most enduring legacy in the sport of track and field. Neither Rome nor Track Town were built in a day.

After Bowerman stepped away from coaching in 1972, the popularity was nearly self-sustaining and his successor, Bill Dellinger, just had to keep it going. He did not stoke the fire quite as well as Bowerman (because hardly anyone else ever has), and interest slowly declined over the next 25 years or so. Then Martin Smith came in as men’s coach, a man who had no interest in working with the community or catering to fans, and turnout for nearly everything at Hayward Field save the Prefontaine Classic declined to levels not seen since Bowerman’s earliest days. Smith was fired and the man hired to replace him, Vin Lananna, understood his dual roles as both a promoter and coach. The phoenix rose from its ashes.

So if you want to build fan interest in your track and field program, you must understand that it’s not a gimmick. It takes a long time. It’s not easy. You are fighting against opponents—in this case, other sports—for whom popularity, not performance, is the #1 priority. And changing the format of the national championship probably isn’t necessary, because it’s the exact same format used forty and fifty years ago, when the NCAAs filled up Detroit’s Cobo Arena every single year.

So what is different about track and field? How did college track look different in, say, 1975 than it does now? There are a lot of things that are different, but I think one of them is the most important.

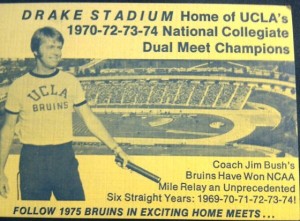

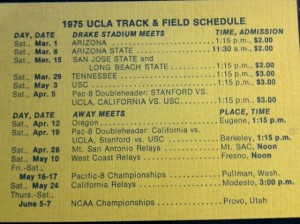

Right here I have two photos from an eBay listing of a cool little knickknack, a 1975 UCLA pocket-sized track and field schedule. The front is an awesome timepiece—check out Coach Jim Bush’s ring T-shirt and stylin’ sideburns—but the back, the Bruins’ meet schedule, is the key.

UCLA competed in a meet for all but two weekends from March 1 all the way to the NCAAs on June 7—thirteen meets in fifteen weeks—and six of those meets were at home. Every team competed this often, and six home meets wasn’t all that unusual. Attendance at the last meet, the dual against USC, was a standing-room-only 15,069. At $3 a head, that’s a nifty $45,207 (worth about $200,000 today).

I’m currently doing some research on early 70s college track, and it’s stunning to see how often athletes competed. The stars ran basically every week, usually including a major invitational right before both the conference and NCAA championships. No one would think of doing that now. The performance level may be higher in 2015, but few are paying attention.

Athletes in modern track and field compete less often than their counterparts in nearly every other sport on the planet. It is track’s most intractable problem. If you want to see Usain Bolt run, your opportunities are not going to come around all that often. While you’re waiting you can easily watch Cristiano Ronaldo, Aaron Rodgers, LeBron James, Yasiel Puig, or Drew Doughty. No surprise that we lose fans to those sports. College track has the same problem; teams compete relatively infrequently, meets that matter are even less frequent, and most teams have only two or three home meets over the entire season.

There is one way for college teams to take things such as they are, with light competition schedules, and make more out of it. The NCAAs are experimenting with single-sex days of competition this June. I think this could work elsewhere, because it attacks two problems at once: our college meets are generally a) too big and b) too few.

For example, when Ohio State and Michigan last met in a dual, the men’s meet was in Columbus while the women’s meet was in Ann Arbor. Each meet felt less cluttered. There was just one team score, the meets were held in a reasonable time frame and no more than three field events were going on at once. I’ve worked a lot of women’s-only meets and they are fun, whereas a traditional men’s-and-women’s meet can be exhausting. Oh, your team has a combined coaching staff and you want to keep the coaches together? Easy, run one meet away on Friday and the other one at home on Saturday, and you don’t even have extra travel.

This is just one suggestion. But if you’re going to attack a problem this big, there can be no sacred cows. Everything has to be on the table.

Can Oregon and Arkansas Win Outdoors?

Oregon beat Florida for the men’s championship. Arkansas beat Oregon for the women’s championship (and almost no one expected the Ducks to finish that high, but I thought they had it in them). Can they do it outdoors?

Indoor track and outdoor track are almost the same sport, but not exactly. Most of the events are the same, a few are different. The 60 and the 100 are a little different but use the same personnel and the final point tally is usually pretty close. This is also true for the 60 and 110 hurdles, the heptathlon and decathlon, and the indoor 3000 and 5000 and the outdoor 5000 and 10,000. The weight throw and hammer are definitely different events, but still they use the same personnel and the results are at least somewhat comparable.

There are five big changes from indoor track to outdoor track. The slate of events adds two long hurdle races (400 hurdles and steeplechase) and two long throws (discus and javelin). The distance medley is swapped for the 4×100 relay. The real question is how these changes affect the top teams from last weekend.

Men: Oregon will lose ten points from the relay swap. They won the indoor DMR and are highly unlikely to score in the outdoor 4×100. They are probably going to at least make that up in the javelin (Sam Crouser, defending NCAA champion) and steeplechase (Tanguy Pepiot, 6th last year). If NCAA champion hurdler Devon Allen can return from his knee injury suffered in the college football playoff and approach what he did last year, then there’s another ten points. As long as the distance runners can do outdoors what they did indoors, then you’re looking at a point total in the mid-70s without Allen and mid-80s with him. Since the current scoring system was introduced in 1985, only once has a team scored more than 57 and failed to win: Florida, last year, with 70.

Florida has a high-profile transfer in T.J. Holmes, who scored a 4th in the 400 hurdles last year, and Eric Futch returns to the same event after redshirting the 2014 season. Another athlete returning from a redshirt is steeplechaser Mark Parrish, who could throw a few points into the hat. Stipe Zunic appears to have pretty much given up the javelin in favor of the shot put (which he won on Saturday), so probably no gain there. The Gators got bumped off the track in Saturday’s 4×400 which cost them about 8 points, and they’ll add anywhere from 5 to 10 points with the 4×100. So this is a point gain of somewhere around 20 to 25 points added to the 50 they scored on Saturday, which gets them into the mid-70s. June is long into the future and a lot of things can change, but right now it looks like a nice battle shaping up.

Women: Arkansas won the distance medley on Friday, so that’s minus-ten for them as they’re not likely to score in the 4×100. 400 hurdler Sparkle McKnight is back from a redshirt year and could score up to 6 points at the nationals. Jessica Kamilos scored 2 points in the steeple at last year’s NCAAs. So at best, it’s a wash for the Razorbacks to go from indoors to outdoors. Put them down for 60 or so points.

Oregon is likely to score more in the 4×100 at the outdoor NCAAs (some) than they did in the distance medley at the indoor NCAAs (none). Haley Crouser could score some in the javelin, and hammer thrower Jillian Weir (6th at last year’s NCAAs) returns after skipping the indoor season. Brianna Nerud has an outside shot at scoring in the steeplechase. On the whole, Oregon has a pretty good chance at scoring more at the outdoor NCAAs than they did at the indoor NCAAs. That’s 50 or so. It puts them in range if Arkansas starts having things go badly–but that’s if the Ducks can recreate the big meet they had this weekend, which may be a stretch.

Two teams that will benefit greatly from the outdoor slate of events are Florida and Texas A&M. The Gators should get some points at the NCAAs in the 4×100 and could get as many as 20 out of the javelin. Texas A&M will be a contender in the 4×100 (they always are) and have the defending NCAA champions in the 400 hurdles (Shamier Little) and discus (Shelby Vaughn), plus a 4th in the javelin. Of the two, I think Texas A&M is the one that might be able to make a run at the title.

Other Random Thoughts

Big Ten

The surprise winner of the heptathlon was Minnesota’s Luca Wieland, who was competing in just the third heptathlon of his college career and became the first Big Ten athlete ever to win the event at the indoor NCAAs. Since the decathlon was added to the NCAA outdoor championships in 1970, just three Big Ten athletes have ever won (Ray Hupp, Ohio State, 1971; Kerry Zimmerman, Indiana, 1983; James Dunkleberger, Wisconsin, 1997).

Akron scored 16 points in the men’s competition, which means they beat the top Big Ten team (Penn State, 15 points). Akron’s women scored 12, which tied them with the top Big Ten team (Wisconsin). The Big Ten is pretty clearly a Power 5 conference in the money sports of football and basketball, but they’re definitely a cut below the other four in track. The last (and only) time the Big Ten won the NCAA indoor championship was in 1997 (Wisconsin), and the last time the conference won the outdoor title was in 1948 (Minnesota). The conference has never won a women’s national track championship, indoors or out.

Pac-12

USC’s Andre De Grasse broke the Canadian indoor 200 metre record on Saturday. The previous record was set last year by Aaron Brown, also running for USC. Brown went on to break the Canadian outdoor 200 metre record last May. Canadian outdoor record holders before Brown were (in reverse order) Atlee Mahorn, Tony Sharpe, Harry Jerome, Mike Agostini, and Lee Orr.

Sharpe set his record in 1982 and in the late-80s Dubin Inquiry he admitted he’d used steroids since 1980, but the mark was never stricken from the record. Mike Agostini competed for Trinidad & Tobago for his entire career save one year—1958, the year he set that Canadian record. As national records go, both of those are a little shaky.

All of the rest competed for Pac-8 teams: Mahorn for Cal, Jerome for Oregon, and Orr for Washington State. You have to go back to the 30s to find a non-Pac-8 record holder. On Saturday, De Grasse made it look like the trend will soon continue.

Providence

Providence coach Ray Treacy had a big weekend. The Friars’ Emily Sisson won the NCAA 5000 on Friday night, and Treacy-coached athletes Amy (Hastings) Cragg won the USATF 15k on Saturday morning and Molly Huddle won the NYRR Half Marathon on Sunday.

NCAA vs USATF

The Portland World Indoor Championships organizing committee had a big press conference yesterday since the meet is now just one year away. One of the announcements was that the 2016 USATF Indoor Championships will be held in the Portland facility on March 11-12, one week prior to the Worlds. These are the exact same dates as next year’s NCAA Indoor Championships.

I think it’s an understatement that it’s not an ideal situation. It means that no US collegians will be able to attempt to make the US team for the Worlds (but foreigners in the NCAAs will be free to compete if their NGB selects them). It also means that the two biggest annual indoor meets will split attention. At first I was shocked and thought it was the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard (and I don’t say that lightly because I teach high school freshmen).

But then I thought about it a bit more. I’m guessing that the facility, the Oregon Convention Center, simply wasn’t available on non-consecutive weekends. Either the cost was prohibitive for the organizing committee, or it was already booked for another gig. If so, that leaves USATF with a tough choice: keep the meet its traditional two weeks prior to the Worlds and turn down possibly the best facility ever constructed in the USA, or bite the bullet and change the date. All things considered, the latter was probably better.

In any case, there are a lot of pros who should thank their lucky stars for this because college kids coming off a full indoor season would be serious competition. The path to the US team just got a little easier.

-

The most important thing to note was that UCLA’s schedule was how many dual and triangular meets there were -with a winning team and a losing team. I grew up with my Dad officiating at Cal meets in Berkeley -and the schedule was the same-and I vividly remember the Double Duals where you could see Cal, Stanford, SC and UCLA on the same day. In my opinion every school should have at least ONE DUAL meet-look at the possibilities Florida-Florida State; Mississippi-Mississippi State; Auburn-Alabama; Texas-Texas A&M; Ohio State-Michigan just to name a few and your idea of splitting the genders is brilliant

-

Regarding the scheduling of the US and NCAA Indoor Championships on the same weekend, I agree that it is not ideal to have them splitting attention. However, how many US collegians would be trying to make the US team for the indoor worlds? My guess is not many. After a long indoor season most top-flight athletes are turning their attention to the outdoor season at that point.

-

So you would prefer that the athletes have less than stellar performances and increased injury risks in order for collegiate track and field to gain more fans? I agree that having more dual and tri and quad meets against rival schools would increase fan interest. During my athletic career at Virginia Tech, I was disappointed that we never had a dual meet against the University of Virginia. Growing up in California, I gained interest in track by watching the dual meet between Cal and Stanford. I agree that athletes should compete in more meets, but not at the expense of their performances. I like the concept of splitting the genders at the NCAA outdoor meet, but I am not sure that most of the athletes are on board with the idea. I will reserve my judgments on that until after the meet though.

-

It comes down to this Fans in the US want to see a winner and a loser and meets with a limited # of schools (especially Duals-Tri’s and Quads) are the only way to go. Would you go to a FB game if all they told you was who the leading rusher is ?

-

My follow up question to this is, where do these large scale invitationals and relay style meets fall into the equation. We can all agree that dual, tri, and quad meets are good for increasing the interest of fans. But do we eliminate large scale invitationals and relay style meets or do we just limit them? And should more responsibility fall on the coaches to foster better community relationships?

-

I think the unscored open meets have their place. I could deal with fewer of those meets but I also understand that those kinds of meets allow unattached athletes to compete. However, that’s another issue in itself and needs more work.

-

Track indeed is hard to build up a fan base largely because it is not promoted by sports networks or the media. It’s sad that the nation with the largest gene pool cannot appreciate events that involve personal perseverance; we as a nation relish the gladiator stuff. In spite of this, I find track to be exciting from middle school to the Olympics. We also have our opponents out there as well. And for the most part, this sport embodies true sportsmanship. Our track opponents pull & push us to better performances. That is the beauty of it. The fight goes on to elevate the sport.

Comments