The Monday Morning Run: Kenyan Marathon Trials, Bromell Goes Pro, De Grasse Says Put

Kevin Sully | On 19, Oct 2015

Two topics this week: Athletics Kenya’s attempt to concoct an Olympic Trials race for the marathon and the professional ambitions of sprinters Trayvon Bromell and Andre De Grasse. First, a few things I learned this week from the road races across the world.

-Fulfilling the prophecy of the Oracle of Fast Names, there is such a person as Asbel Kipsang. He won the Lisbon Marathon in 2:09:26.

-Keep an eye on 19-year-old Shure Demisa. In her third marathon, she ran 2:23:37 to win in Toronto. And this was the race for second…..

That’s not the ideal way to finish a marathon. #STWM http://t.co/LCc8g97kor pic.twitter.com/V4eOLiFmAT

— Chris Nickinson (@chrisnickinson) October 18, 2015

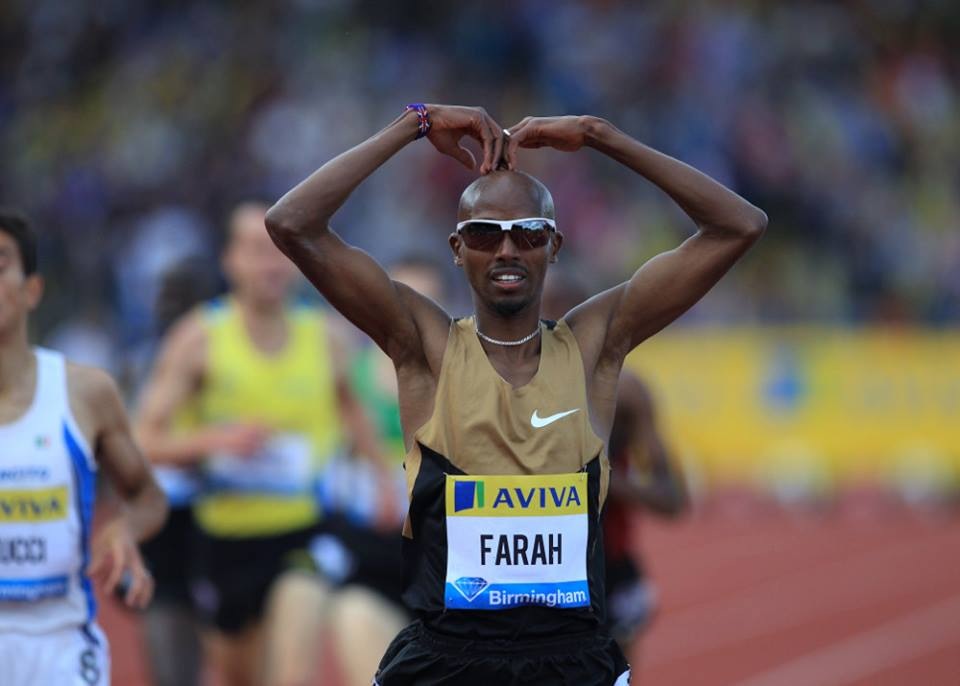

-Also at the Toronto Marathon, men’s race winner Ishimael Chemtan did the Mobot. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. If you can’t join ‘em, imitate their celebration in a race they aren’t running.

-A ton of fast people run the Amsterdam Marathon. The names on the entry list probably knock Chicago down to the fourth best marathon of the fall, at least for the men. If the World Marathon Majors wanted to expand (which they shouldn’t), Amsterdam is a deep enough race to fit right in. Bernard Kipyego (2:06:19) and Joyce Chepkirui (2:24:11) were the winners on Sunday.

–Abraham Cheroben ran the fastest half marathon of the year, a 59:10 clocking in Valencia.

Kenyan Olympic Trials

Let’s be clear, a Kenyan Olympic Trials for the marathon would be awesome. Trials races already are a wonderful spectacle of tension. Add in the fact that it involves the best marathon running country in the world and you’d have a must see event–at least in the minds of running nerds. If they set a qualifying time that allowed the best 200 or 300 runners by time they’d have a field large enough to included the obvious favorites, but also some unknown runners who could pull an upset give the opportunity. There is an everyman quality to the marathon. With fewer barriers to entry than events on the track (and even more so in other sports), it’s actually incredibly simple to be an elite marathoner. Find a race, run it quickly. That same formula applies to an Olympic trials race, which also embodies the same spirit of meritocracy. Find a race, run the qualifying time and you are in. Finish top three and you are an Olympian. The playing field is level at the Trials–it doesn’t matter if you are a gold medalist or the last qualifier. Everyone has an equal chance on that day. This is why trials are so interesting for fans. You are drawn into the race because of the who might finish first, but what you remember is who came in third.

That sort of story in Kenya would be fascinating. In distance running there is an idea, real or perceived, that there are countless elite runners in Kenya bubbling just below the surface. If given the right opportunity in a race like the trials, maybe one of them could surprise and grab a spot on the team. In most cases the Mary Keitany and Wilson Kipsang’s will win out, but there is still an opportunity. At the very least, it’s much better than the typical ways Kenya has selected their team. These methods have included a race within a race, which obviously excludes a great number of runners, and the governing body selecting who they thought the best to represent the country at the Olympics. Neither option worked very well. Both felt below such a great marathoning nation. Even if you take the Cinderella component out of it, a trials race is the only fair way to separate the myriad of Kenyan runners at the very top.

Anyway, that’s a very long way of saying I think Kenya hosting their own Olympic Trials for the marathon for the first time in history is a great idea. Give them a few years to find a suitable venue and get together some sponsors so they can offer huge prize money and it’s a can’t miss.

Then I learned that this wasn’t an idea for the 2020 Olympics, but for next year. As in four months from now.

That’s right the greatest distance running nation in the world scheduled their most important race of the year with about as much planning as your friend’s beer mile over Thanksgiving. Forget preparation….after all how much time does it really take to get ready for a marathon?

I assumed that if Athletics Kenya wanted to host this race that they’d actually, you know, tell the athletes with more than four months notice. Give them some warning so they can, you know, train for the race. But Athletics Kenya went right along scheduling their theoretical trials. Because of the reasons listed above, I doubt the race comes to fruition. Even if athletes hadn’t already scheduled their fall and spring races, it is still too much to ask to give someone four months notice for a race. Nothing in major sports is planned in four months. Actually, nothing in any sport is planned in four months. Youth soccer schedule are mapped out with less haste.

And even though it won’t actually happen, this becomes another chance for Athletics Kenya to spotlight its inability to grasp simple concepts of the sport. They botched the 2012 Olympic marathon selection by bypassing Geoffrey Mutai. They tried to limit the amount of Diamond League races Asbel Kiprop and others competed in last summer. The documentary that uncovered doping in Kenya also alleged mishandling of Nike funds by Athletics Kenya.

It’s track and field so every governing body is a little goofy, but no country’s athletes succeed more in spite of their country than Kenya. In the case of the Olympic Trials, it’s too bad. A Kenya mega-race would have been fun to watch. They just should have planned it two years ago.

Bromell Turns Pro, De Grasse Stays Put (for now)

In the week that Trayvon Bromell announced that he is foregoing his collegiate eligibility to run professionally, his NCAA rival, Andre De Grasse looks like he will remain in college. Initial reporting had De Grasse also going pro, but his mother told the media that her son is remaining at USC and that he hadn’t signed with an agent. These two will be forever linked by their incredible NCAA careers and also their World Championships tie in the 100m when they both ran 9.92.

Their late season success in 2015 counters the idea that competing in the NCAA system and doing well at the major championships in late August are mutually exclusive. It’s hard enough to time a peak once, let alone twice. Yet, both men did it this year. In winning bronzes, they beat Tyson Gay, Asafa Powell, Jimmy Vicaut– experienced professional runners who had the luxury of only worrying about the World Championships all season.

So if it worked last year, why is Bromell changing for the Olympic year? Because he’s not really changing anything. He plans to stay in the same city and remain with the same coach. The only difference is he isn’t going to run as frequently and when he does he will be compensated for his abilities. Sounds like a good deal.

Bromell is only 20, but the window for elite sprinters to cash in is relatively small. According to Sporting Intelligence, “The top 10 fastest male sprinters in the world stopped improving as a group by about age 25 for the 100m and 23 for the 200m.”

With that information, it’s hard to argue against maximizing your earning potential while your times are still dropping. Of course Bromell will still be able to make a living on the track even as he ages into his late 20s. But it’s a safe assumption that his best chances at an Olympic medal come in 2016 and 2020. One of those opportunities, of course, is next year.

With Bromell gone, De Grasse should have a free reign of the 100m and 200m in the NCAA season. His NCAA double last year was the best of all-time and he still looks like he is getting better with each race. Bromell has been running close to sub 10 since high school so there is reason to believe he might even be younger than 25 when he stops dropping time. Not so with De Grasse. He essentially just started running seriously so his peak should come later. Perhaps that factors into his decision to stay amateur. Why turn professional until you’ve run a time that aligns with your value as a professional? All of that is guesswork. Maybe it’s Bromell who continues to drop time and De Grasse flattens off at a younger age.

Because he is Canadian, De Grasse’s situation is slightly different from Bromell’s. De Grasse has an easier path through Olympic qualifying. There is not the same high stakes trials process as Bromell. If he’s not at his best at the end June, it doesn’t matter. He can still round into shape on his own timeline and not worry about losing a spot on the team for Rio. Bromell doesn’t have that luxury. The margin of error on the U.S. 100m team is so small that in most years he has to be in sub 9.90 shape to finish in the top three.

Despite running the same time in Beijing, much of their experience in track is different. De Grasse’s decision to stay in the NCAA might just be another way these two have take a different approach to end up at the same spot.

Submit a Comment