24 Hours 'Til 26 Miles: Craig Leon and the Chicago Marathon

Kevin Sully | On 15, Oct 2014

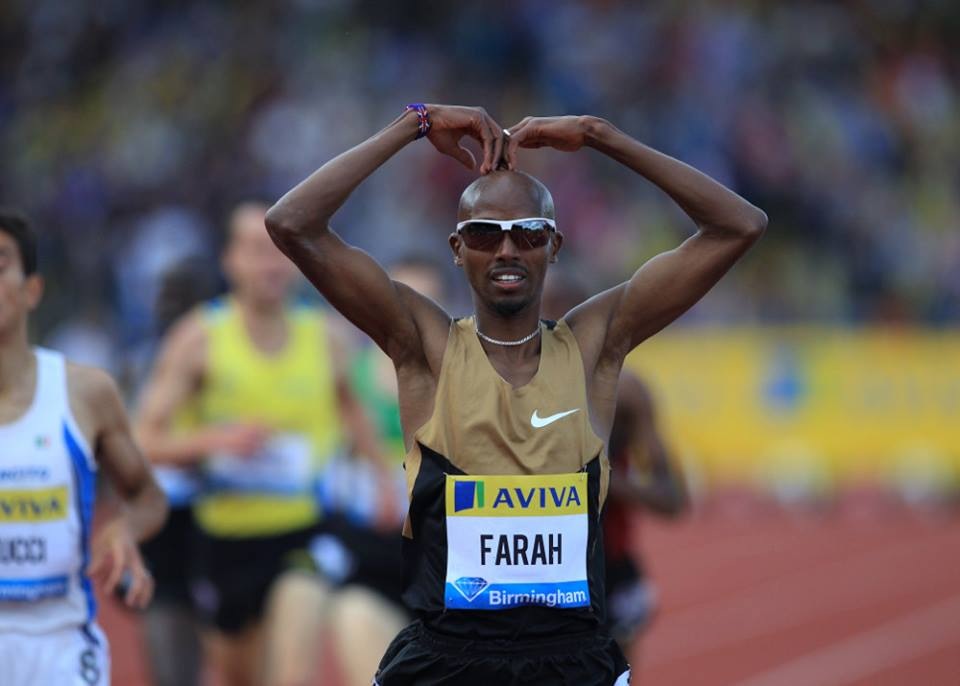

Photo via @CleonRun

The first floor of the Chicago Hilton is a flurry of activity. Professional athletes, regular runners and race staff are mixed together, all seemingly walking in different directions. Some are heading out into the morning for one final jog. Others are coming back in from a cool, clear morning. Defending champion Rita Jeptoo walks past a man in a bright orange “13.1” shirt toward a bank of elevators with her picture on them.

Twenty-four hours from now there will be order. Tomorrow, all the attention will be across the street when the marathon begins with its 45,000 runners.

Just before 7:30, Craig Leon enters the lobby. He’s already been awake for two hours. It was habit, not pre-race jitters that made him get up 90 minutes before the sun. He’s usually up this early — running twice a day while holding down a job doesn’t leave time for lazy mornings. So on a day like today, when he could grab a couple hours extra sleep, instincts kick in. With his roommate still asleep, he answers emails for his job at the University of Oregon’s sports marketing school, goes on a walk to Grant Park and makes a stop at CVS.

After all those tasks are complete, he meets me in the lobby. I’m there to see how an elite marathoner spends his final hours before all of his training and preparation is put to the test. He’s here to do one final run before he takes on the ninth marathon of his career.

The Run: 7:40 a.m., Saturday, Oct. 11

We head out to Grant Park for an easy four-mile run. The group includes his coach, Ian Dobson, fellow elite Alexi Pappas and two of Craig’s college teammates from Ohio University. They call it a shake-out run and the route’s proximity to Lake Michigan gives it the name “shake by the lake.” Typically, Leon runs a workout of 2 x 1-mile at race pace the day prior to a marathon. Today, he scraps that plan and instead goes with something lighter. After running 120-150 miles per week in his main training block, he knows that one modified workout won’t hurt him in the race tomorrow.

We follow the Lakefront path that hugs Lake Michigan and snakes past the Shedd Aquarium and Soldier Field. Pappas, who is also coached by Dobson, is pacing the women’s race tomorrow and is trying to figure out a new GPS running watch that will help her run the correct splits. She jokingly holds her arm up to the sky, hoping to get a better signal. “That’s not how it works,” Craig says.

The mood is light. It’s hard to feel anything less than optimistic with the weather. Craig is wearing a jacket, pants and gloves, but he knows the chilly 45-degree temperatures are perfect for Sunday. All eight of his previous marathons have had ideal temperatures. If the conditions hold, tomorrow will mark nine in a row. “It’s part of my pitch when I talk with race directors,” he says. “Bring me in and I can promise you good weather.”

As Leon bounces along the bike path, I get a chance to speak with Dobson. He likes Craig’s progression and thinks a personal best is a reasonable target. Coaching during the race is a difficult task. With three athletes in the race, Dobson will only get to see Craig probably two or three times on the course.

Fifteen minutes pass and we turn around and run back. A cyclist shouts “Good luck marathoners” to the group. The sunshine has everyone in high spirits.

We arrive back at Grant Park and Craig finds a concrete strip to do strides and stretches. He tears off his pants and accelerates. Finally unleashed after the morning jog, you can see the efficient stride and quick turnover that make him capable of running five-minute miles for 26 miles.

I ask Craig’s former teammates if they ever thought Craig would be this good. He was, after all, a walk-on in college and wasn’t an NCAA All-American.

No doubt, they say.

“He loves running more than anyone I’ve ever met,” one his teammates says.

As the race draws closer, you see the relentless positivity. He’s not stoic or terse. You’d have no idea that tomorrow is one of his two opportunities per year to run a major race.

His outlook is complemented by Craig’s compatibility with the distance. A “grinder,” he finds himself adapting to long training sessions quickly. He says he can’t run a 400 in under 60 seconds, but he can repeatedly pile up big mileage weeks without a problem.

After the last stride, and with his final run complete, he pulls his pants back on and walks back toward the hotel. “It feels good to be done,” he says. “This is the fun part.”

Breakfast: 9:00 a.m.

Fifteen minutes after the run, Craig is dressed for breakfast in an orange Chicago Bears hat and a Chicago Marathon sweatshirt. A native of Van Wert, Ohio (a town of 11,000 located 220 miles east of Chicago), he still pulls for Chicago sports teams.

The crowd in the hotel is growing and a line for the marathon expo shuttle wraps around the block. He walks down Michigan Avenue to his favorite breakfast spot in Chicago, Yolk. Along the way a man with a fake Irish accent greets everyone who passes by.

”Good morning, whippersnappers!” he says as we walk past. “That guy was in the same spot last year,” Leon says.

The restaurant is filled with marathoners and the typical Saturday morning breakfast crowd. Sun shines through the glass front doors and bounces off the blue and yellow accents on the walls. The waiters wear shirts that say, ”Handling your huevos since 2006.”

Two more of Craig’s friends join us to make a party of six.

There’s no pre-race anxiety at the table. Not from Craig or his friends, two of whom are also running tomorrow. He enjoys not talking race strategy and instead tries to get caught up on their lives. They discuss college friends, life in Ohio and that night’s Chicago Blackhawks game. One buddy back in Ohio is planning to leave a homecoming celebration in the middle of the night to catch the end of Craig’s race.

Invariably the conversation does turn to running. They ask Craig what they should eat and where the best spots on the course are to cheer.

The menu is expansive. He doesn’t have a lucky pre-race meal and doesn’t consider himself a creature of habit. Still, some parts of the menu are off limits. “Definitely getting the stuffed French toast tomorrow — probably getting two tomorrow.”

After some deliberation, he decides on something he’s never had — an “iron man” omelet with potatoes and wheat toast on the side. He finishes most of the omelet and all of the potatoes and toast. The meal wraps up a little after 10. As the group walks back toward the hotel, they make plans to meet up after the race. Craig returns to the Hilton and his friends head off to explore the city.

Uniform Check: 10:35 a.m.

The hospitality suite for the elite athletes is located in the Imperial Suites on the Hilton’s eighth floor. It is here where Craig goes for his uniform inspection. All pro athletes must have their uniforms checked to ensure that they are in compliance with IAAF regulations regarding the size of the logos.

I’m not allowed into the inspection, but Craig tells me after that they measured the sponsor logos with a sheet of paper that designates the maximum size. Both of his logos, one of his sponsor, Mizuno, and the other of his club, Team Run Eugene, are cleared for competition.

Lunch: 11:05 a.m.

Next on the agenda is a lunch with his footwear and apparel sponsor, Mizuno. Chris Hollis, Mizuno’s grassroots running manager, meets us in the lobby. He is joined by the local Mizuno representative and two other Mizuno athletes who are racing tomorrow, Christo Landry and Patrick Rizzo.

Despite sharing a sponsor, the three don’t live in the same part of the country and really only see each other at races. The marathon is a good excuse for all them to get together. Hollis hands Craig a box of red and black Mizunos. “Bulls colors!” he says before dropping them off at his room.

The group chats about lunch location and eventually settles on — Yolk. The crowd has swelled since this morning and they opt for another place with a shorter wait. We backtrack and head up Wabash Avenue to the Eleven City Diner.

The hostess at the front tells us where to go for Bloody Marys or mimosas. Not today. Like the rest of the city, the restaurant is at capacity on marathon weekend. We grab a table upstairs. Initially, Craig doesn’t plan on getting anything. Breakfast was just an hour ago, but when the waitress asks, he orders yogurt, fruit and granola.

Hollis tells the group that shoes and gear are waiting for them at home. They chat about future racing plans and the recent 20K in New Haven in which a spectator jumped into the lead pack, creating an unexpected photo opportunity.

After Lunch: 12:45 p.m.

After two meals, a run and several walks, Craig is finally able to take his shoes off again. He’s back in a room on the ninth floor of the Hilton with his Team Run Eugene teammate, Dan Kremske. The room is crowded with clothes and gear for tomorrow’s race. On the dresser is a carbon copy of a drug testing form from the United States Anti-Doping Agency. Friday, a doping control officer knocked on the door and took a sample of Craig’s blood.

I ask about his expectations for the race. He’s never been the top American in a major marathon, but tomorrow he has a good chance. For him though, the goal is time and not place. At the Olympic Trials and Boston Marathons, he will focus on where he finishes. Tomorrow in Chicago is about the clock.

If other Americans run faster, so be it, he can’t prevent that, or as he says, “You can’t play defense in running.”

His goal is to set a personal best and hopefully run under 2:13. In his first attempt at the distance in 2010 he ran 2:23:15. Since then, he has consistently knocked off time.

With the weather and his experience with the distance, he thinks 2:13 is attainable. And though he isn’t looking too much into where he finishes, this race will help him figure out where he stands about 16 months out from the Olympic Trials Marathon.

Bottle Check: 2:40 p.m.

The rest of the day’s events are closed to the media, but Craig filled me in on the specifics. Before he attends the technical meeting, there is one final bit of logistics. Craig and the other elite athletes check in their water bottles with the race staff. He will fill all eight of his bottles with water and two scoops of blueberry pomegranate GU “electrolyte brew.”

The bottles will be placed in eight different boxes, one for each 5K marker on the course. Athletes are also able to decorate the bottles so they can more easily identify which to grab during the race. Markers, pipe cleaners, tape and other arts and crafts supplies are typically made available during bottle check. Some even build their own handles on the bottles.

Craig keeps it simple. His bottles will be the ones with no decorations. His roommate, Kremske, opts for a little more flair and wraps leopard print duct tape around the center.

He has learned a couple tricks in his previous races. “I made the mistake before of not filling bottle up the all the way,” he says.

A half-filled bottle causes a few problems.

First, it is harder to grab on the run because the weight isn’t distributed evenly. Also,

if there is more fluid then he will be more inclined to take in more fluids. He has made it a point to hold on to his bottles longer, a tip he picked up from Olympian Ryan Hall, who sometimes carries his bottle with him for more than a quarter of a mile.

In additional to the fluids, he will also bring three energy gels with him. He tucks those into his pockets. He’ll take the first one between miles 8-10, the second between 18-20 and keep the third in case of an emergency. ”I only have had to go to the third one once.” That was during his first race in Chicago when he missed three of his bottles.

Technical Meeting: 3:30 p.m.

The technical meeting occurs the night before every major marathon. Elite athletes and their managers meet with the race director to run through the final details for race day. They discuss what time breakfast is, where to meet for the bus and how fast each of the pacesetters will run. It’s the last point that athletes and fans are most interested in. The lead group is scheduled to hit halfway in 1:01:40.

Craig is hoping to latch onto the pack that is running 2:12 pace. He wants to hit the halfway point between 1:05:40 and 1:06:00 giving him some padding to meet his 2:13 goal.

A perfect race for him includes that 1:06:00 split with a pack of six to 12 runners staying intact through 18 miles. But he knows dream scenarios in a marathon rarely work out. He is willing to run by himself if necessary, which means spending time and energy keeping a pace. ”Magic isn’t made inside a controlled setting, ” he says. ” I don’t think you can control the marathon like you can a track race.”

Dinner and Beyond: 4:30 p.m.

After the meeting, all the elite athletes head to dinner. It’s a buffet style meal and usually features salad, pasta and chicken. One item he won’t have is dessert. He gave up sweets, along with alcohol, two months ago. At 9:00 p.m. he is in bed where he hopes to fall asleep by 9:30 or 10:00 p.m.

The Race, Sunday, Oct. 12

Craig wakes up at 4:30 a.m. and eats oatmeal and a banana. Even though the start line is walking distance from the hotel, a bus takes the athletes to Columbus Drive. There, they sit in a heated tent as the race draws closer. Music combine with the energy of the city echo to create a sense of excitement around them. Craig jogs 10-12 minutes before the race, just enough to get the blood moving. At 7:30 a.m., the race begins.

After passing the halfway point in 1:06:05, Craig slows over the final eight miles to finish in 2:16:00. He is the seventh American across the line. Ironically, it was the weather that ended up preventing fast times.

“One of the first things I noticed when I peered out the window of our bus on the way to the start line were the freely blowing flags hanging from the buildings on Michigan Ave.” he wrote on his website after the race.

“Part of me wanted to believe that it was just a gust blowing through the tunnel of buildings. There was no way it could be windy; none of the forecasts had wind.”

The “tactical error” he says, was in not adjusting his early pace to compensate for the wind.

“Rather than just easing off slightly, we continued to fight the wind and the stretch from 7.5-13 [miles] ultimately zapped me (probably safe to say, us) of having the energy to run well over the last half of the race.”

Despite not hitting his time goal and losing his perfect weather streak, he left Chicago optimistic. “Running is still fun, and even the worst day of racing is better than not having the opportunity to be living out a dream.”

Submit a Comment