What does Mo Farah have in common with Larry Page?

Ben Enowitz | On 12, Jun 2013

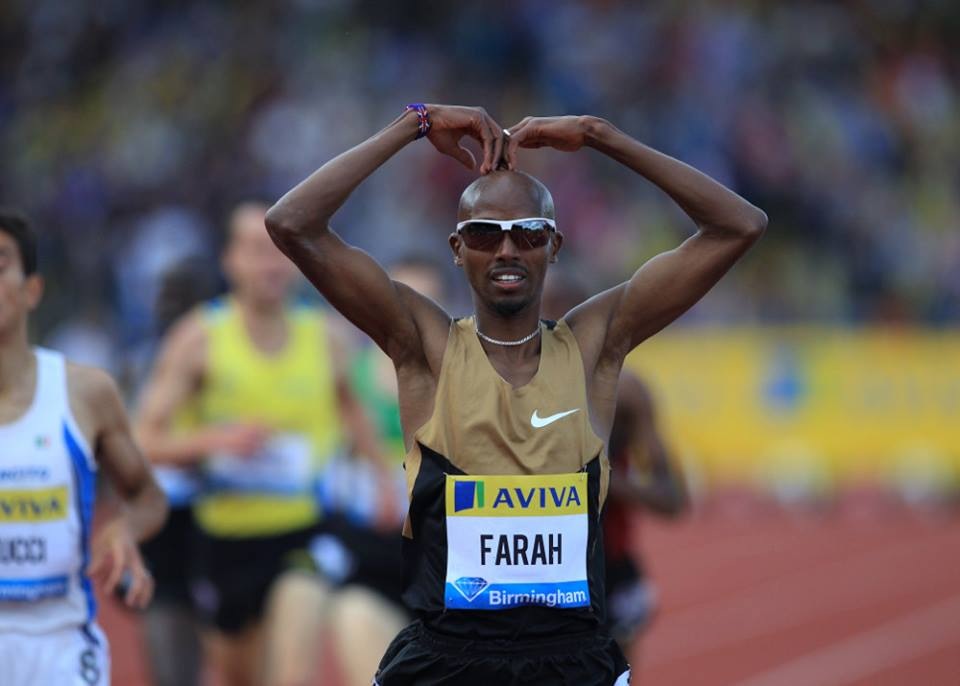

Photo courtesy of tracktownphoto.com

It’s the Olympic 5,000m final. Every runner and coach has spent the last couple years planning out how the race will unfold and how their dreams of Olympic gold could be realized. Dreams of ripping a fast last 200 in a slow, tactical affair. Dreams of leading a long sustained drive from 1,000 out, holding off all the kickers. Dreams of winning in any and every possible way. Unfortunately for the athletes, the race rarely goes to plan. At each step the runner must make a decision, sometimes deliberately pushing the pace, other times unconsciously moving with the pack and often times slowing down uncontrollably.

Mo Farah, Galen Rupp, Bernard Lagat, and Dejen Gebremeskel among others are standing on the start line of the 5,000m Olympic Final, each with a legitimate chance to win gold. The race starts out slow, a couple of laps at 70 seconds before picking up slightly. With five laps to go, Gebremeskel gets the race going with a 60-second lap. The crowd starts cheering as Farah takes the lead with 700 meters to go. With one and half laps left, Farah and Rupp really start pushing the pace. Farah is in the lead with a lap to go. 400 meters until glory. He holds off each of the respective moves from Thomas Longosiwa, Abdalaati Iguider and Koech before hitting the line first.

It wasn’t a shock that Farah won, but it probably was a surprise when people looked at the scoreboard and saw a relatively pedestrian 13:41.66. Call it tactics, call it strategy or call it running scared, but sometimes a stronger field only leads to a slower winning time. Much to the chagrin of the fans, the runners understand that championships are about medals, not times.

Perhaps game theory can help us understand why a slow, tactical final is the norm.

A primer on game theory

One of the best examples of game theory is called the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Imagine you’re a criminal who, along with your co-conspirator, is arrested for robbing a bank. What would you do when asked to testify against your criminal partner?

You both know that if you both stay silent and don’t testify against one another then you will each spend a year in jail. However, if you both turn against each other and testify against each other in hopes of avoiding any jail-time, you will each serve two years of jail. A third possibility is you decide to testify against your partner, and your partner stays silent. This means you get to go free and he takes the full punishment and spends three years behind bars. Conversely, you may decide to stay silent and not rat out your partner. However, if your partner testifies against you, he will go free and you will be locked up for 3 years?

What should you do to minimize time your time in jail?

The answer is relatively simple. If Prisoner B stays silent, it is best for Prisoner A to betray (betraying means Prisoner A goes free whereas staying silent means serving 1 year). If Prisoner B betrays Prisoner A, then it is better for Prisoner A to also betray Prisoner B (Prison A then serves two years for betraying rather than serving 3 years for staying silent). Thus, the optimal strategy for Prisoner A is to always betray. The same logic applies to Prisoner B, meaning he should also betray Prisoner A. This solution (where each Prisoner opts to betray the other) is called a Nash equilibrium, leading to each Prisoner serving 2 years.

It is puzzling that the optimal solution where each Prisoner stays quiet (this solution is optimal because total time in prison is only two years, one for each prisoner) is not the equilibrium and the solution that maximizes time in prison (total of years) is the equilibrium.

In running there is a similar phenomenon. One where runners do not cooperate to maximize their chances of winning much like the prisoners who do not cooperate to reduce their prison time. The field goes out timid, each runner trying to avoid being the sacrificial lamb that often becomes of the early pacemaker. For better or for worse, the race comes down to the kickers. It may be in the best interest for a couple strength-oriented runners to agree to break off early, alternate laps and sap the kick out of the field. Such a strategy may very well lead straight to the podium. However, if often leads to tears of disappointment. The pack stalks the leader, slowly speeding up and pounces only when they think they will take the lead for good.

When to kick?

Nevertheless, the question remains: when should you start to kick? Farah took the lead with around 700 meters out and started slowly ratcheting down the pace until reaching a full sprint from 200 meters out. In 2004, Kenenisa Bekele took the lead with 200m to go only to be passed by Hicham El Guerrouj in the last 50 meters to win the 5,000. There are usually many sure ways to lose a 5,000 and it is up to the runner to figure the one way to maximize their chances of winning.

One of the best parallels to the conundrum of a runner is the “first mover advantage” in business. Corporations often have the choice between spending years waiting for new products to result from research & development or cheaply replicating a new product of a competitor that has just been released. The tradeoffs are clear. Move first through research & development (“R&D”) and you can create a new product that leads to massive profit before your competitors can react—you’re the first mover. But the company also risks wasting capital on costly R&D that may lead to a failed product. The second approach is to spend less on R&D and wait for a competitor to create a new, successful product and then cheaply replicate it. The company that waits won’t have this first mover advantage, but does save money that would have otherwise been spent on development. The risk is the competitor creates a product, like the iPod, that then becomes the de facto standard and gains too much of a lead to ever be replicated and gain wide appeal.

Larry Page, the CEO of Google, is deciding each day to spend time and money to develop self-driving cars. It may lead to the ultimate profitable product or it may end up in the Google product graveyard along with Google Reader, Google Buzz and Google Wave, with the final count showing many years and dollars invested with no return.

This is similar to the runner’s dilemma in championship races. Mo Farah spends the entire race wondering what to do next. Move first and you can sap the energy from the kickers, but also risk burning out early. Sit calmly in the back of the pack and wait for others to waste energy upfront, could lead to a definitive move in the final 250m or questions in the mixed zone about why you waited too long to make a move.

–2013 NCAA 800m Champ, Elijah Greer of Oregon talking about his tactics during the PAC-12 800m run.

The answer is as unclear and unpredictable in track as it is in business. Maybe in the next couple years we can get Stashies at Nashies to not only be the standard at NCAA Cross Country Championships, but also the new trend for attending Game Theory 101 classes. Better yet, maybe we will soon see Larry Page or even Larry Summers joining the Nike Oregon Project as strategic advisors.

-

Enowitz is track and field. Track and field….is Enowitz

-

What about the Nash Equilibrium?

-

“Better yet, maybe we will soon see Larry Page or even Larry Summers joining the Nike Oregon Project as strategic advisors.”

Don’t give Alberto ideas, Ben! Great piece as always.

Comments