I Heard the News Today, oh boy

Jesse Squire | On 14, Jul 2013

No doubt you’ve already heard the news that came out today: Tyson Gay tested positive for a banned substance back in May. Five Jamaicans also tested positive at the Jamaican Championships last month, reportedly being Asafa Powell, Nesta Carter (not “officially” named yet), Sherone Simpson and two lesser known throwers (and maybe a jumper). Rumors of other positives are going around. It all came out in one morning.

Is this sad? Disappointing? The death of track and field? Victory in the war against doping? It’s probably a little bit of all of them.

It’s a victory for the anti-doping system in that it caught offenders. It’s sad and disappointing not because these people were caught, but because they did something to catch. On the other hand, if anyone is shocked, shocked to find corruption going on in sport, well I guess you don’t read business or political news much. Corruption is a fact of life in any highly competitive arena in which humans take part. It’s why we have laws and regulations and enforcement, and why self-regulation is laughable on its face. And I don’t think track and field is any more corrupt than other sports; in fact, I think it might be considerably less.

Let’s play a game of “what if”. What if two large states, say California and New York, had vastly differing approaches to political corruption. One state, maybe California, had stringent anti-corruption rules. Reporting forms had to be filled out regularly. An entire enforcement agency was created and funded and kept out of the influence of political parties. The other state, say New York, had lax rules, basically no reporting system, and what little enforcement existed was highly easy hijacked by political insiders.

Which state would take down more of its public officials? No doubt it would be California. Would that mean it was more corrupt? Not at all. New Yorkers might want to say that, but it wouldn’t be true. And that’s what we have in sports.

By now, anyone who has more than a passing interest in sports knows that track and field and cycling are singularly aggressive in enforcing anti-doping rules. Baseball is less so, but it still stands out among the major North American pro sports as being willing to suspend its own players. Tyson Gay testing positive is the functional equivalent of the NFL giving Ray Lewis a significant suspension, which wasn’t ever going to happen no matter what he did.

If there is something upsetting, it’s that Tyson Gay was one of the first 12 athletes to sign up for USADA’s “Project Believe”, a precursor of sorts to the biological passport program. The fact that a guy who signed up for extra monitoring ended up with a positive test makes you wonder if you can trust anyone. The cynic in me says that’s right, the world is an ambiguous and uncertain place where few people deserve your complete trust and certainly no celebrities do. (Well, maybe Tom Hanks. But that’s it.)

As it just so happens, this morning’s stage of the Tour de France went up the Mont Ventoux. The modern anti-doping movement began on that same mountain, forty-six years and one day ago, when Tom Simpson died on the ascent. Drugs were found in his pocket and in his system. Nowadays the major reason for anti-doping rules is that fans find drug use distasteful, but it’s important to realize that the most basic reason for doping controls is that, given the chance, athletes will quite literally kill themselves to win. I think that strong doping controls make high-level sport more interesting by leveling the playing field, but they also make it something you would want your children to do.

Track and field is about to join cycling on the list of sports that are officially dead

— Philip Hersh (@olyphil) July 14, 2013

I’m not a big fan of Phil Hersh’s bombast and this statement only underscores that. If cycling is “dead”, why is it on TV for eight hours a day over an entire month? Track and field has never once been that alive in this country.

(As an aside, how much worse could it get? Outside of Eugene, where track and field is alive and well and thriving, Tyson Gay has run in front of a U.S. crowd of 10,000 or more just once since his breakout season of 2006. It’s a bit like the scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian where a man condemned to stoning is told he’s only making it worse for himself, to which he replies, “Making it worse?! How could it be worse?!”)

In the 80s when I was young and biked a lot (not competitively), the Tour de France coverage on US television amounted to weekend highlight reels. In the 90s the Tour started being shown on Outdoor Life Network (which morphed into Versus, which morphed into NBC Sports), and not too long after that was when Lance Armstrong began his drug-fueled series of victories. Americans discovered the Tour and began to love it.

Nowadays we all know that most cyclists used to dope and we suspect that some still do, and no Americans are remotely close to the top of the standings. And yet the Tour is still on TV, all day, every day, and Americans watch it. That’s because the cyclists aren’t actually the stars. The star is the grand spectacle, the beautiful French countryside and mountains and villages, the startlingly weird fans who line the course. The masses have discovered something that two decades ago was little more than a cult following in the USA, and it’s all great fun. All sports, to a degree, depend on big spectacles. Take the English Premier League commercials running on NBC–they’re not hyping the players or the teams or even the on-field action so much as the incredible match-day atmosphere.

Track and field will survive just as it always has because we too have that great spectacle. For us it’s only once every four years, but it’s magnificent, a great celebration of internationalism and brotherhood and all that other stuff the IOC talks about and we know is bulls*** but we love anyway.

There are other pockets of great spectacles here and there in U.S. track; most any meet at Hayward Field, the big relay carnivals, the major marathons, some state high school championships. If you show any of these to sports fans they will like it, and none of them are going away any time soon.

So it’s not a question of what to do when we lose a few stars in an extreme minority of events–and make no mistake, that’s what today’s news really is. It’s a question of what we are going to do with everything else we have to showcase. And we have plenty.

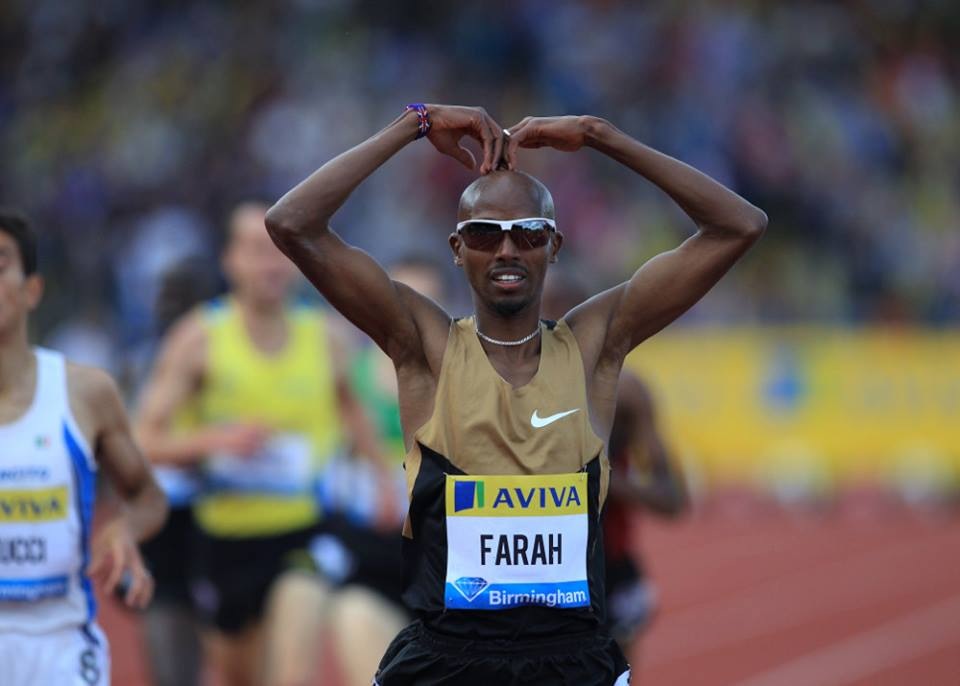

Great marks from Donetsk, Tampere, Paris, Birmingham. But the world talks about something else. The fight must continue. Anyway.

— Alfonz Juck (@emenews) July 14, 2013

Comments