The Worlds' Most Memorable Moments, part 2

Jesse Squire | On 29, Jul 2013

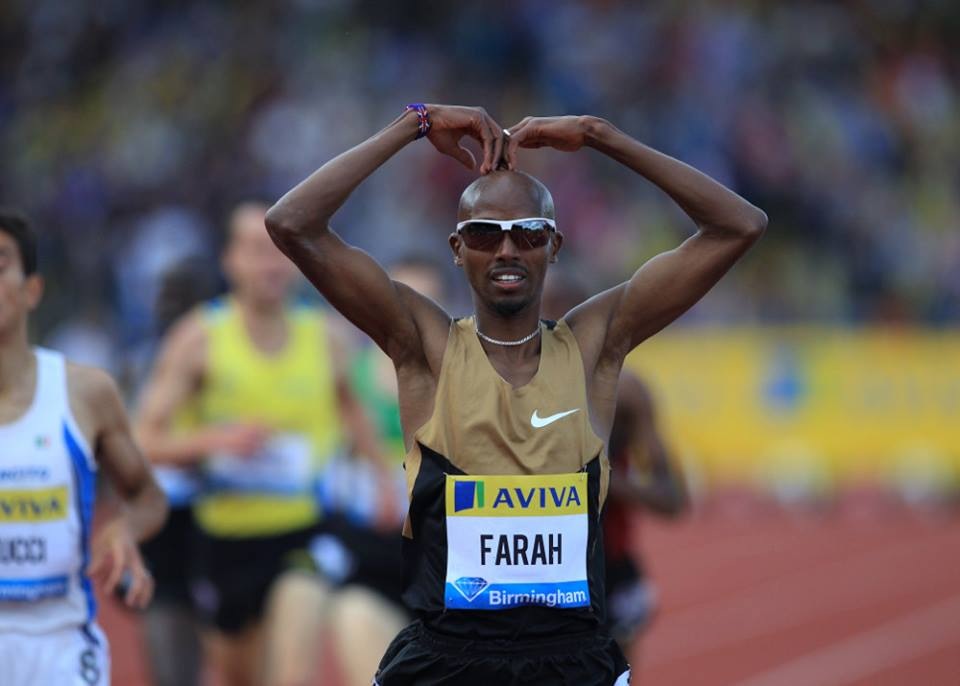

42 kilometers done, 200 meters to go. (Photo by Jesse Squire.)

Yesterday I kicked off a countdown of the most memorable moments in World Championships history. Since the first Worlds were held thirty years ago, I’m choosing thirty moments.

Once I started digging into this, I found it remarkable how many great moments I had to drop in order to cut it down to thirty. I’m striving for a balance across events and years, and realize that “memorable” and “great” aren’t always the same things.

Here we go!

20. Marathon sprint finish

Edmonton, 2001

Olympic opening ceremonies have become amazing displays of pageantry and showmanship, with millions of dollars spent on them in front of a worldwide audience of hundreds and hundreds of millions of viewers. The World Championships have opening ceremonies, too. But can you recall ever seeing any of them on TV? There’s probably a reason for that, and it’s because they’re usually fairly boring. Usually, but not always.

I went to the 2001 Worlds in Edmonton and my recently-widowered high school coach went with me. We had the time of our lives. The package we got from Track and Field News Tours included tickets for all sessions, so we went to the opening ceremonies but didn’t expect a whole lot. We were so wrong.

The dance numbers were odd. The parade of nations dragged on. The Mounties marching onto the field were cool. But the organizers struck gold with one idea: the men’s marathon, traditionally the last event on the schedule, instead kicked it off. They started on the track at the beginning of the evening. On-course updates were periodically shown on the stadium videoboard. And at about three-fourths of the way through the opening ceremonies, the show stopped to let the runners return to the stadium for their last three hundred meters.

John Crumpacker, writing in 2001 for the San Francisco Chronicle:

With 60,000 fans awaiting their arrival back in Commonwealth Stadium, Gezahegne Abera of Ethiopia and Simon Biwott of Kenya waged a tremendous battle for the gold medal. Since Ethiopia and Kenya are to distance running what North Carolina and Duke are to college basketball, it was an intense duel indeed.

Biwott, tall and with the loping stride of a basketball player running the court, entered the stadium marginally ahead of Abera, the Olympic champion at Sydney. After nearly 26 miles, the race was on.

The crowd roared as the two East Africans stepped up into sprint mode. With 200 meters to go, the Ethiopian surged ahead of the Kenyan and won the gold medal — and $60,000 U.S. dollars — by one second, 2:12:42 to 2:12:43. Such is the rivalry between the two countries that neither man congratulated the other or so much as offered a hand to shake for a job well done.

In fact, Abera and Biwott did not even acknowledge each other’s presence after the race, when they accepted their national flags and walked a victory lap.

Offering up a sanitized response, Biwott said, “Ethiopia and Kenya are very good neighbors. They are our neighbors. We respect each other. Whenever we meet, there is always good competition. It’s never easy.”

Video of this finish is hard to come by, but it’s burned into my memory.

19. Eamonn Coghlan wins 5000 meters

Helsinki, 1983

Coghlan was a big celebrity in the late 70s and early 80s, both in Ireland and the USA. The four-time NCAA champion went on to dominate stateside indoor competition, the first to gain the moniker “The Chairman of the Boards”. Three times he broke the world indoor record, all in the United States, taking it all the way down to a stunning 3:49.78 in 1983–the fastest mile ever run in the USA, indoors or out, until 2007.

But this tremendous indoor success did not translate outdoors. Coghlan finished fourth and out of the medals in the 1976 and 1980 Olympics, took silver at the ’78 European Championships, and missed the ’82 Euros with injury. At 30 years of age, the ’83 Worlds was one of his last real chances to win gold.

The story according to Athletics Ireland:

By any standards, Eamonn Coghlan’s 1983 was an exceptional year; first that sensational world indoor mile record of 3:49.78 for the man known universally as Chairman of the Boards, then later in the summer, the inaugural IAAF World Championship 5,000 metres title – a landmark achievement in Irish athletics.

In those seven months period from February to August, Eamonn seemed almost invincible, and to athletics enthusiasts everywhere, but especially here in Ireland, he became one of the all-time greats…

That victory in Helsinki was one of the greatest moments in Irish sport. Eamonn ran the perfect race, third at the bell, making his move 300m out, and by the time they hit the home straight it was all over – 13:28.53, and the last 1,000m at sub-four minute mile pace. Everyone remembers his jubilation at the win, and at 30 years of age it was no more than he deserved.

That win will live forever in our memories…

Coghlan remains Ireland’s only male gold medal winner at the Worlds.

18. Simpson’s surprise win

Daegu, 2011

The women’s 1500 is not one of the USA’s strengths. The Stars and Stripes could claim just one Worlds gold medal (Mary Slaney ’83) and three others (bronze in ’09 by Shannon Rowbury, two silvers in ’97 and ’99 by the notorious Regina Jacbobs). The Olympic total is total futility: zero medals of any kind.

That changed in 2011, when Jenny Simpson became a surprise world champion–and no one appeared more surprised than Simpson herself. Sports Illustrated’s Brian Cazaneuve:

“Jenny Simpson, are you going to the moon?”

Nope, that’s not it. This was a look of shock and awe, a willing suspension of disbelief, caught in a moment of hope and uncertainty.

“Jenny Simpson, did you just win the lottery?”

Sorry, try again. It was wide-eyed amazement, euphoria tied up under some thought that it might just be a dream.

“Jenny Simpson, you’re a world champion?”

That’s the scene. If ever the thrill of victory had a pinch-me freeze frame, there it was. And the response was absolutely appropriate: Simpson was just a rookie miler on the international circuit, competing in an event she was coaxed into by injury. She was the national runner-up in an event no U.S. athlete had won on the world stage in 28 years, crossing the line ahead of presumptive favorites at the World Championships in Daegu last month.

“With 400 meters [left], I was not thinking I was going to win,” recalls Simpson, who at that point was still near the back of a tightly bunched pack. “With 150 meters to go at the top of the turn, I was beginning to count the people in front of me and I was thinking, ‘I could get a medal.’ I had so much left, and I was watching women fade into my peripheral vision.”

One by one, she passed runners from Ethiopia, Morocco and Spain and finally the aptly named Briton Hannah English. “I was focused on the scoreboard waiting for some kind of confirmation,” Simpson says. “What have I just done? Was it real? I was waiting for someone to hand me a bouquet of flowers or shake hands, so I knew.” It isn’t as if Simpson had propelled herself from nowhere, because her training times suggested she had it in her. But competition calls you out – it either lifts you or freezes you.

17. Weis wins hammer on final throw

Athens, 1997

Jon Hendershott summed up the wild action in the November ’97 issue of Track and Field News:

…one of the most thrilling field event competitions in recent memory found the lead changing hands no fewer than ten times. Germany’s Heinz Weis eventually whirled the longest effort–268-4 (81.78)–on the last throw of the day.

The 34-year-old German, seasonal leader at 272-5, finally prevailed over Andrey Skvaruk (267-3) and Vasily Sidorenko (264-11).

…

Sidorenko took the lead in round one at 256-9 (78.26), extending it to 259-6 (79.10) in frame 2. Weis then hit 263-3 (80.24) on his third toss to move in front.

When the order reversed for the final three throws, Sidorenko reclaimed first at 263-8 (80.38). To close the round, Weis reaced 264-2 (80.52). Back to Sidorenko in round 5 at 264-11 (80.76). As the video screen replayed that heave, Weis whirled the ball out to 266-2 (81.14).

Enter Skvaruk in round 6. Standing sixth, the Ukranian exploded to 267-3 (81.46), punching the air as the ball flew away. Sidorenko, suddenly third, closed at just 256-11 (78.32). It was all left for Weis.

So the 6’4″ / 265 lb. Weis spun out his winner, screaming his usual “fliege!” (fly) after the implement. He then jumped into the arms of teammate Karsten Kobs before sharing a flag-waving victory lap with Skvaruk.

16. Sally Gunnell sets WR

Stuttgart, 1993

Gunnell was already the Olympic 400 meter hurdle champion the year before and she admitted she felt tremendous pressure to repeat as champion. She had a great rivalry with Sandra Farmer-Patrick (“We had a lot of respect for each other but we weren’t the best of buddies, we didn’t exactly talk much”), and Farmer-Patrick was determined to turn the tables.

The American took the pace out hard and had a clear lead by the fourth hurdle. Gunnell closed on the turn and briefly overtook the lead before Farmer-Patrick again edged ahead. Over the final forty meters, Gunnell closed and finally went ahead for good. Both broke the old world record.

“I couldn’t be sure that I had won,” said the Briton, “so I didn’t start celebrating in case I made a fool of myself.”

15. Wami kicks to 10k win

Seville, 1999

Before Paula Radcliffe was a marathoner she was a tremendous track and cross country runner, but she lacked one thing: a kick. She was fearless, though, and would try anything no matter how crazy. Here’s how Reuters called in in 1999:

Gete Wami outsprinted Paula Radcliffe yet again to become Ethiopia’s first women’s world champion with a sizzling last lap in the 10,000 meters Thursday.

The twice world cross country champion crossed the line in a championship record 30 minutes 24.56 seconds, the fourth fastest time ever.

“The race was extremely tough, it was very hot out there. But I was confident of my kick and counting on going past the other girls,” Wami commented.

Briton Radcliffe, who was beaten in similar fashion by Wami at the world cross country championships in March, led for much of the race but again was found wanting for finishing speed when the gold medal was decided and had no response when Wami stepped on the accelerator with 200 meters to go.

Although the finish had a sense of history repeating itself, it was also the climax of an enthralling race conducted for the most part between three runners.

Radcliffe had decided beforehand that the only way to win the race was to set a brutal pace from the gun and hopefully pull the sting from the rest of the competitors. The Briton passed through the halfway point in 15:25.24 and then surged again, increasing the tempo.

All the other chasing women were shaken off, except for Wami and Kenya’s Tegla Loroupe. Loroupe, the holder of the women’s world marathon best, briefly took the lead with 11 laps to go but before long it was Radcliffe who was back in front.

With barely three laps to go Loroupe again tested Wami and Radcliffe but it was to be a another brief bid for glory and the honors eventually went to Loroupe’s East African neighbor.

14. Merlene Ottey loses close finish

Stuttgart, 1993

Bitter postrace arguments weren’t uncommon in the days of calling race winners by the human eye, but once cameras and computers got involved it quieted down. Not in this one, though. Here’s how former TFN managing editor Jeff Hollobaugh wrote about it for ESPN.com:

As much as this race mirrored other fantastically close dash finishes we have seen from the top women over the past decade, it also highlighted the great differences in the attitudes of the winners versus the losers.

Four women figured to be in the mix: Gwen Torrence, Russia’s Irina Privalova, Jamaican Merlene Ottey, and Gail Devers, attempting a dash/hurdles double. Privalova led for much of the first half of the race before succumbing to the speed of Devers.

Ottey then pulled even with the compact American in the final meters, and appeared to have a slight lead with a step to go. Then Devers threw her body into a lean at the finish, while the tall Jamaican remained relatively upright.

Replays of the stadium video didn’t help the crowd separate the two. Finally, the announcer hailed Devers as the winner, 10.81 to 10.82. The Jamaicans immediately protested. Said Devers, “The protest doesn’t bother me at all. I need to focus on the hurdles now. This race is over.”

Ottey told the press, “If the protest goes against me, it will be the wrong decision.” After a couple hours, the panel, not unanimously, declared Devers victorious, with a corrected time of 10.82. The photo showed a margin of just 0.004 seconds, or one centimeter. Ottey lashed out, “I’m the champion. They made a mistake but won’t admit it.”

13. Kluft wins a close heptathlon

Helsinki, 2005

I think every writeup I’ve seen on this heptathlon battle between Carolina Kluft and Eunice Barber used the word “epic”. :

World heptathlon champion Carolina Kluft retained her title on Sunday after an epic two-day battle with France’s Eunice Barber.

The 22-year-old Swede overhauled Barber in the finishing straight of the concluding 800 meters to clinch gold, having taken an 18-point advantage into the final event.

…

By contrast, Britain’s Kelly Sotherton performed disastrously in the javelin to slip back to fifth place and needed a strong performance in the 800 meters to claim the bronze. She took up a stong early pace, tracked by Barber, who had to beat Kluft by 1.3 seconds to claim the gold.

Barber came onto Sotherton’s shoulder in the final 200 meters but then weakened to be overtaken by Kluft who powered up the closing straight to claim global gold yet again after her triumph in the 2004 Olympics in Athens.

…

Kluft, unbeaten in the heptathlon and any multi-events competition for almost four years, finished with 6,887 points. Barber, as she did in Paris two years ago, took silver with 6,824.

Kluft had nursed an ankle injury throughout the competition and trailed Barber overnight by two points.

It’s hard to rank competitions but I think this was the toughest heptathlon I’ve ever done,” Kluft told a news conference. “It was really tough for me to keep going, this was a great experience for me and I’m just happy I made it.”

Kluft said the injury to her left ankle, which she twisted in falling awkwardly in training on Friday, had played on her mind but had also forced her to approach the competition in a different way.

“It was tough to get into it, the high jump (the second event) was very bad for me. I had to motivate myself to maintain a positive spirit. I learned not to get upset when things don’t go my way.”

Barber, who has returned to form this season after an injury-plagued 2004, was left to rue what might have been. Leading overnight by two points, the 30-year old had her advantage wiped out in a controversial long jump after the French team unsuccessfully protested that Kluft had fouled on the take-off board in registering a 6.87 meter leap.

Both athletes saw it differently. Kluft, renowned for her sportsmanship, said: “It was very very close but it (her foot) was not over.” Barber, however, believed the decision not to uphold the appeal had been “unfair”. “She clearly fouled,” she told reporters.

Barber blamed her defeat on her own mistakes though, saying over-enthusiasm got the better of her, particularly in the long jump and javelin.

12. Michael Johnson sets WR

Seville, 1999

Witnessing a World Record is a transcendent experience, but in 13 editions of the World Championships there are enough that by themselves they don’t always merit placement in this all-time ranking. You need a record that, as Nigel Tufnel would say, goes to eleven.

Johnson torched the 200 meter world record at the 1996 Olympics but found the 400 record much trickier to beat. He tried for years before he could get past the 43.29 set by Butch Reynolds some 11 years earlier. SI’s Tim Layden:

He lay sprawled on the track in twilight, his chest rapidly rising and falling like a sleeping infant’s. On the infield grass a clock illuminated 43.18 in yellow, along with the simple message NEW W.R. Michael Johnson stared at a darkening Spanish sky and at a full moon above the Seville Olympic Stadium, and then he ended a decade’s pursuit of that 400-meter record and three years of injury and frustration with one crooked smile.

…

But in the end the spotlight in Seville belonged—surprisingly—to Johnson. His world record in the 400, which broke Butch Reynolds’s 11-year-old record of 43.29 (which had snapped a two-decade-old mark), gave Johnson his sixth individual world championship gold medal, and it was redolent of his surpassing 19.32 record in the 200 in Atlanta. Johnson’s performance in Seville was all the more remarkable considering that as recently as three weeks earlier he was actually considering retirement.

In early August, Johnson drove the 90-plus miles from his home in Dallas to Baylor, his alma mater, in Waco to brainstorm with his coach, Clyde Hart, and to train in the bludgeoning Texas heat. It’s a drive that Johnson has made hundreds of times in the last decade, but this visit was different. “When he walked into my office that day, Michael was at a lower point, physically and mentally, than I’d ever seen him,” says Hart. “He was very, very down.”

It had been a long, downward spiral from Atlanta. In June 1997, Johnson injured his left quadriceps in the disastrous 150-meter World’s Fastest Human match race with Canadian 100-meter Olympic gold medalist Donovan Bailey and pulled up 70 meters from the finish line. Afterwards Bailey accused Johnson of quitting to save face, a charge that was echoed by much of the media. He put himself back together to win the world 400 title in Athens that summer, but much of the season was lost to the injury that he had in fact suffered in the match race. His ’98 campaign was similarly undercut by injuries.

…

Hart listened and then spoke. “What was our goal this year?” he asked Johnson.

“World record in the 400,” Johnson answered.

Hart pointed at the watch on his left wrist. “There’s still time,” he said.

…

Just before leaving for Seville, he produced one of the best workouts of his life: three 350-meter sprints, each run in 44 seconds, with five minutes’ rest between them. Upon arriving in Spain, he ran two more 350s in an average of 43 seconds (the second in a searing 42.6) in 100° heat. “Faster than before Atlanta, so fast I was scared,” said Hart. With his body fit, Johnson exercised his psyche by meeting a small group of journalists before the start of the championships to clear the air. It was entirely out of character and apparently liberating. The Johnson who ran in Seville engaged media, fans and volunteers as if he were the ebullient Greene. He bore little resemblance to the sphinx who won in Atlanta.

He then ran the most startling 400 in history. By turning in a blistering 43.95 in the semis despite shutting down 100 meters from the finish, he raised expectations that he would break the world record. He didn’t disappoint. In the final he ran the first 200 in a controlled 21 seconds flat, towing most of the field with him. “Then, right after the 200, Michael just took off,” said U.S. runner Antonio Pettigrew, who was two lanes inside Johnson, after the race. “He just ran away from us. It was the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen.”

While seven other runners clawed at the air, Johnson drew away by 15 meters. When he crossed the line, the clock flashed 43.19 and then was adjusted downward by .01 of a second to reflect the actual time. The second place finisher, Sanderlei Claro Parrela, was more than a second behind. “He didn’t even pull anybody along because he was so far ahead,” said Pettigrew. “If somebody had been with him, he could’ve run 42.6, no doubt.”

11. Harting goes berserk

Berlin, 2009

It can be memorable to win in front of a loving and excitable home crowd, or to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat at the last moment, or to celebrate in a wild and crazy manner. Put them all together and you’ve really got something.

Discus thrower Robert Harting is a Berlin resident, so the fans payed attention when he stepped into the ring at the 2009 Worlds.

Elliot Denman, for Milesplit:

They adore their musclemen in this part of the world.

The behemoths are beloved. They fill stadiums. Every time they flex a bicep, the crowds go bananas.

Oh, not for skills playing defensive tackle, middle guard or strongside linebacker. Just for whirling two-kilogram plates through the night air, whirling 16-pound balls-and-chains great distances, or muscling cannonballs 20 or 22 meters.

You had to be at Olympic Stadium Wednesday night to believe any of this.

Harting won the competition on his final throw, ending Gerd Kanter’s year-long win streak, and the crowd went crazy. Then Harting went crazier, sprinting around the track and tearing his jersey Hulk-style, tossing the mascot like a ragdoll.

“The support was really tremendous. I had hoped that may be a couple of chairs would have been ripped out and thrown down on the track,” he said. “I will surely not go to bed before tomorrow evening! We will now really celebrate and spend some money.” And when a German says he’s going to party, you should stay out of the way.

Werner Gegenbauer, president of the Berlin soccer team and who played a large role in bringing the Worlds to Berlin, offered to allow Harting to use his “superfast Audi” for a week if he threw over 68.50 meters. Noting his winning distance of 69.43, “Believe me,” Harting said, “I will do as many traffic offences as possible!”

The video really has to be seen to be believed.

Tomorrow: the top ten. Every last one is amazing.

Related Posts

The Monday Morning Run: A-Z Guide to the US Championships... June 22, 2015 | Kevin Sully

Moscow Daily for August 14 August 14, 2013 | Jesse Squire

-

July 30, 2013

Ralph McGinnisMr. Squire, the 2011 World Championships was held in Daegu, South Korea, not Osaka, Japan, which held it in 2007.

Comments